At 84, American political scientist Gene Sharp has seen his lifelong work on nonviolent resistance echo around the world.

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- Political scientist Gene Sharp has been called the father of nonviolent struggle

- Sharp wrote a manual on how to overthrow dictatorships, "From Dictatorship to Democracy"

- Sharp says no regime can survive without the support of its people

- Arab Spring put a new spotlight on Sharp's work

Gene Sharp: A dictator's worst nightmare

June 25, 2012

London (CNN) -- It's a dark January evening, and in an anonymous townhouse near Paddington station, a man is talking about how to stage a revolution.

A young Iranian asks a question: "The youth in Iran are very disillusioned by the brutality of the violence used against them ... It has stopped all the street protest," she says. "What would you say to them? How can they get themselves organized again?"

The man thinks for a moment. He's an unlikely looking radical -- slightly stooped with white hair, his bent frame engulfed by the low chair he's sitting in.

When he opens his mouth to speak, all eyes in the room are fastened on him.

"You don't march down the street towards soldiers with machine guns. ... That's not a wise thing to do.

"But there are other things that are much more extreme. ... You could have everybody stay at home.

"Total silence of the city," he says lowering his voice to a whisper, punctuating the words with his bent hands, as if he's wiping out the noise himself.

"Everybody at home." The man's eyes scan the room. "Silence," he whispers again.

"You think the regime will notice?"

He looks around the room, nodding almost imperceptibly. On the wall behind his head hangs a huge print of the Hiroshima atomic bomb mushrooming into the sky.

This is political scientist Gene Sharp, and explosive ideas are his specialty.

Gene Sharp, who wrote "From Dictatorship to Democracy," says no regime can survive without the support of its people.

RUARIDH ARROW

He's been called the father of nonviolent struggle. He could be also described as a revolutionary's best friend. Or perhaps, more accurately, as a dictatorship's worst nightmare.

Now 84, the American academic has dedicated most of his life to the study of the bold, some might say reckless, idea that nonviolence -- rather than violence -- is the most effective way of overthrowing corrupt, repressive regimes.

On this winter night, he's talking at The Frontline Club, London's journalism hub, and it's standing room only.

Those without seats have crowded in at the back of the room under a huge photograph of a girl offering a flower to a line of riot police. She could have been inspired by Sharp's writings.

His practical manual on how to overthrow dictatorships, "From Dictatorship to Democracy," has spread like a virus since he wrote it 20 years ago and has been translated by activists into more than 30 languages.

He has also listed "198 Methods of Nonviolent Action" -- powerful, sometimes surprising, ways to tear power from the hands of regimes. Examples of their use by demonstrators and revolutionaries pop up over and over again.

In Ukraine, during the 2004 Orange Revolution that propelled opposition leader Viktor Yushchenko to electoral triumph, hundreds of thousands of demonstrators turned Kiev's Independence Square into a sea of orange flags -- the color of Yuschenko's campaign.

No. 18 on Sharp's list: Displays of flags and symbolic colors.

In Serbia, activists fighting then-President Slobodan Milosevic in the 2000 presidential elections printed "Gotov Je!""He's Finished!" on stickers, T-shirts and posters to help the population understand he was not invincible.

No. 7 on Sharp's list: Slogans, caricatures and symbols.

In Cairo during last year's

Egyptian revolution, protesters lived in a tent city in Tahrir Square, where they produced art, made music and sung anti-Hosni Mubarak songs. Many Egyptians would gather there for Friday prayers followed by mass political rallies.

Nos. 20, 37 and 47 on Sharp's list: Prayer and worship. Singing. Assembling to protest.

His ideas of revolution are based on an elegantly simple premise: No regime, not even the most brutally authoritarian, can survive without the support of its people. So, Sharp proposes, take it away.

Nonviolent action, he says, can eat away at a regime's pillars of power like termites in a tree. Eventually, the whole thing collapses.

For a half century, Sharp has refined the theory of nonviolent conflict and crafted the tools of his trade. His methods have liberated millions from tyranny -- and that makes regimes from Myanmar to Iran quake in their boots.

In 2009, he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. During the Arab Spring uprisings, his methods were cited repeatedly.

The applause comes after "decades of hardships," he says. His methods have been dismissed and misinterpreted -- he's even been accused of working for the CIA.

But he's kept on with "the work," sometimes near penniless. He runs his organization, the Albert Einstein Institution, out of his home in East Boston because he cannot afford office space.

He'll give almost anyone a half hour of his time, even a high school kid doing a project. And the pilgrims come.

They come from all over the world because they want to change their situation. They come to hear the extraordinary ideas that Sharp has stubbornly built over a lifetime: ideas that have started revolutions.

The first rebellion

When Sharp graduated college in 1951, he moved to New York and worked odd jobs to put food on the table. He spent his spare time holed up in the New York City Library working on a book about the Indian political leader Mahatma Gandhi, who he still loosely describes as his hero.

He was also dodging the draft.

The U.S. was fighting the Korean War, and Sharp was refusing to cooperate with the military draft board. He wouldn't report for physical examinations or carry a draft card.

"I had chosen a particular kind of conscientious objection, I guess the most obnoxious kind that existed -- civil disobedience."

It amounted to draft evasion, a criminal offense punishable by up to 14 years in prison.

His father, a Protestant minister, and mother were distraught. He was an outstanding student. Why was he throwing away his future?

"They put all kinds of strong, strong pressures on me," he remembers. But he continued. "It was just something I had to do and be done with it."

At first, Sharp applied for conscientious objector status but was refused. Then he changed his mind: "I realized I shouldn't have done it in the first place, I shouldn't have applied for it."

And when the board finally did give it to him, he wouldn't accept it.

By 1953, things weren't looking good for Sharp. He had been arrested by the FBI and locked up in a federal detention center, awaiting trial. But during this tough time, he had an unlikely and important ally: Albert Einstein.

Sharp was just 25, but already he displayed the intellectual chutzpah that would come to characterize his later work. He wrote to the physicist, asking him to pen the foreword to his book and telling him about his court case.

A notable pacifist in later life, Einstein shared Sharp's admiration for Gandhi. He agreed to write the foreword.

"I earnestly admire you for your moral strength and can only hope, although I really do not know, that I would have acted as you did, had I found myself in your situation," Einstein wrote in a letter dated April 2, 1953.

Einstein also wrote the foreword to Sharp's book, describing it as "the art of a born historian" and adding: "How is it possible that a young man was able to create such mature piece of work?"

Sharp used Einstein's name in a speech he made at his trial. In the end, he was sentenced to two years in prison.

His mother, Eve, who had traveled from Ohio for his sentencing also wrote to Einstein. And he wrote her back. Her son, he told her, was "irresistible in his noble sincerity." The letter was, Sharp says, "a big help" to his parents.

In the end, Sharp served nine months and 10 days.

"You count the days in those places," he says now, adding that if he hadn't followed his conscience, it would have been tragic for him.

"I would not have had the self-respect and internal integrity to go on and do in the future what might lie ahead."

Eureka moment

After his release from prison, Sharp concentrated on his work once again.

After a short spell in London as an editor at the pacifist journal Peace News, he moved to Norway where he joined the Institute for Social Research in Oslo.

"It was the first time I had financial support to do my own research and my own thinking and my own writing," says Sharp.

He had been invited by philosopher Arne Næss, who shared Sharp's interest in Gandhi and who, much later, would gain prominence as the father of environmentalism.

For a while, things looked promising. Næss persuaded the institute to fund a major research program into nonviolent conflict.

That's a great advantage -- to know what you don't know. You have a chance of learning -- if you want to and you're not arrogant.

Gene Sharp

But almost before it got off the ground, it was bypassed in favor of a new and more fashionable area of study: peace research.

To this day, Sharp has refused to allow his work to be absorbed into the grander narrative of Peace Studies, losing out on immeasurable funding.

"I still think a lot of the peace researchers are quite naïve and romantic under the guise of science," he says.

Amazingly, Sharp was kept on at the institute to do his own research for a couple of years. It was there that he laid the foundations of his work, tapping out page after page on his little portable typewriter.

But in Norway, Sharp also began to see the flaw in his work: He didn't understand political power.

"That's a great advantage -- to know what you don't know," he says now. "'You have a chance of learning -- if you want to and you're not arrogant."

So he returned to England to pursue a degree in political science at The University of Oxford. He studied under Alan Bullock, the first biographer of Adolf Hitler, reading everything from Machiavelli to Auguste Comte and David Hume; analyses of totalitarianism; histories of dictatorships.

And as he put the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle together, Sharp started revising his work and asking critical questions.

What gives a government -- even a repressive regime -- the power to rule? The answer, he realized, was people's belief in its power. Even dictatorships require the cooperation and obedience of the people they rule to stay in charge.

So, he reasoned, if you can identify the sources of a government's power -- people working in civil service, police and judges, even the army -- then you know what a dictatorship depends on for its existence.

Once he'd worked that out, Sharp went back to his theories of nonviolent struggle: "What is the nature of this technique?" he asked himself. "What are its methods ... different kinds of strikes, protests, boycotts, hunger strikes ... How does it work? It may fail. If it fails, why? If it succeeds, why?"

Suddenly, he got it. If a dictatorship depends on the cooperation of people and institutions, then all you have to do is shrink that support.

That's when the light went on in Sharp's head. That is exactly what nonviolent struggle does. By its very nature, nonviolent struggle destroys governments, even brutal dictatorships, politically.

It is a weapon as potent as a bomb or a gun -- maybe more so.

"That was the eureka moment," says Sharp. He remembers sitting in his little room in Oxford, shocked and, he says, relieved.

"This was not just a theory. This was actually something that had been applied in many different historical cases."

That moment would evolve into Sharp's first big text, "The Politics of Non-Violence," which was published in 1973. It was immediately hailed a classic and is still considered the definitive study of nonviolent struggle.

The viral pamphlet

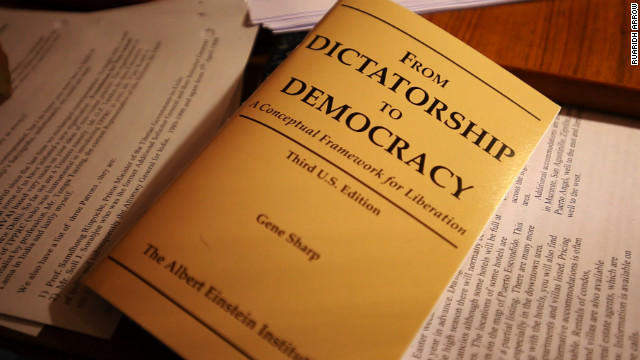

Sharp's best-known work, "From Dictatorship to Democracy," is a how-to manual for overthrowing dictatorships.

It started life in Myanmar as incendiary advice printed on a few sheets of paper and surreptitiously exchanged by activists living under a military dictatorship. Those found in possession of the booklet were sentenced to seven years in prison.

From Myanmar, it was taken to Indonesia, then to Serbia. After that, Sharp says, he lost track of the book. But it took on a life of its own, spreading from activist to activist and eventually, some say, inspiring the uprisings known as the Arab Spring.

Ahmed Maher, a leading organizer of the April 6 Youth Movement that played a key role in last year's Egyptian revolution, told The New York Times that the group read about nonviolent conflict.

He said some members of the group traveled to Serbia to exchange ideas with members of The Centre for Applied Non Violent Actions and Strategies . The Belgrade-based institution was formed in 2004 by former members of Otpor!, the youth group that helped overthrow Slobodan Milosevic in 2000 using Sharp's methods.

Political Scientist Gene Sharp wrote a manual on how to overthrow dictatorships, "From Dictatorship to Democracy."

RUARIDH ARROW

Journalist and filmmaker Ruaridh Arrow, who made a documentary about Sharp's work called "How to Start a Revolution," was in Egypt during last year's revolution. He says a young activist told him Sharp's work had been widely distributed in Arabic, but he refused to talk about it on camera for fear that knowledge of the U.S. influence would destabilize the movement.

Sharp has written about 30 books and has a 900-page guide to self-liberation available for free download on his website. He says military people often have taken his work more seriously than pacifists.

"They could understand the clashing of forces and the use of strategy and tactics."

One such convert was Robert Helvey, a retired U.S. Army colonel who met Sharp at Harvard University in 1987.

Sharp was director of the Program for Nonviolent Sanctions at the Center for International Affairs at Harvard, and Helvey, a decorated Vietnam veteran, was a senior fellow there.

Helvey's experiences in the Vietnam War had convinced him that there had to be an alternative to killing people. After hearing Sharp speak, he was hooked. Myanmar, Helvey decided, was the perfect place to bring Sharp's theories.

Helvey had been a U.S. military attache in Rangoon (the former capital of Myanmar, now called Yangon) and had become sympathetic to groups opposing the regime. After leaving the army, he started doing consultancy work for the Karen National Union, conducting a series of courses on nonviolent struggle for the leadership of the democratic opposition.

The Burmese were amazed by Sharp's theories. They couldn't believe they had been fighting and killing for 20 years when there was an alternative.

The late U Tin Maung Win, a prominent exiled Burmese democrat, asked Sharp to write something for them.

"I couldn't write about Burma honestly because I didn't know Burma well," Sharp says, "and you should at least have the humility not to write about something you don't know anything about.

"So I had to write generically -- if there was a movement that wanted to bring a dictatorship to an end, how could they do it."

Clearly, the news is getting around that nonviolent struggle exists. And clearly it comes almost as a revelation to people that they are not helpless.

Gene Sharp

And so, "From Dictatorship to Democracy: A Conceptual Framework for Liberation" was born.

Today, the book has been translated into Amharic, Farsi, French, German, Serbian, Tibetan, Ukrainian, Uzbek, Arabic and dozens of other languages.

"Clearly the news is getting around that nonviolent struggle exists," says Sharp. "And clearly it comes almost as a revelation to people that they are not helpless."

Despite the Arab Spring pushing his work into the spotlight in 2011 like never before, Sharp remains skeptical about his actual, measurable influence.

"Even today, I'm credited with some major influence in Egypt, for example," he says. "I haven't seen hard data that would prove that."

Einstein's legacy

Today, Sharp spends much of his time running the Albert Einstein Institution -- the organization he founded in 1983 to spread his ideas and secure some much-needed funding, something he's struggled with his whole career.

"(Nonviolent struggle) was not credited with being realistic or with being powerful," he says.

It's a shoestring operation with outsize influence that he runs alongside Executive Director Jamila Raqib. She's his right hand; a subtle organizing influence, watchdog and second brain when Sharp's memory occasionally fails him.

She also supervises the people who come from all over the world to visit Sharp, allowing her to see his influence on those struggling against tyranny or living under a dictatorship.

They come from India, Syria, Russia, Sri Lanka -- from all over. They leave, says Raqib, "with stars in their eyes."

"There's something happening," she adds. "Oftentimes people would say, you know, 'This can't work for us, my situation is unique, my situation is worse, the repression is particularly harsh.'

"And what he does during those conversations ... they leave with the understanding that, you know ... a seed has been planted; a new possibility is there."

Sharp sees himself as a kind of mentor.

"I always refuse to tell them what to do. I'm trying to get them to realize that they understand maybe more than they thought they did.

"There's one phrase that's been quoted -- 'Dictatorships are never as strong as they think they are, and people are never as weak as they think they are.'"

Earlier this year, he released "Sharp's Dictionary of Power and Struggle: Language of Civil Resistance in Conflicts." He says the major unsolved problems of our time -- genocide, dictatorship, war -- require us to rethink the very language we use to define them.

His dictionary contains some 900 terms. It reconceives many words we take for granted -- such as power or defense. "The defense force -- sometimes they attack," Sharp says.

The institute also supervises translations of Sharp's work into other languages -- a task made more complicated by the precisely defined concepts.

They rely on activists for translating, rather than professional translators, because they understand the nature of the work the words describe.

For Sharp, the language is crucial: "If our language doesn't have clear meanings and accurate meanings, you can't think clearly.

"If you can't think clearly, you have no ability to evaluate or influence what happens. So the distortions of our language help make us helpless."

Sharp has no plans to settle into a comfortable retirement, not now, when things are finally taking off.

He admits that he "gets tired sometimes." But there's so much to do.

"The last few weeks I've been waking up in the middle of the night and finding some ideas ... or a solution to a problem I've been trying to solve for a week or two or three."

At the Frontline Club, the questions from the audience keep coming. Sharp's answers, more than anything, underscore his modesty and lack of pretention.

What about government defectors who want to join freedom groups, asks another Iranian. When should you allow them in and when should you reject them?

"An outsider like me can't tell you what to do," he says, "and if I did, you shouldn't believe me. Trust yourselves.

"You've got to be smart. This takes time and energy ... know your situation in depth."

For those who are serious, Sharp has a condensed version of what he says are the required readings of his work, a guide to self-liberation, available free on the Albert Einstein Institution website.

"It's only 900 pages in English," he deadpans, raising a chuckle.

"And if you're not interested in reading 900 pages, you're not interested in getting rid of the dictator," he retorts, whip smart. "Quite seriously."

At the end, people crowd forward to speak to him, kneeling at his chair as if he were royalty, asking him to sign copies of his books.

Later, as he's helped into his flecked black coat and handed his walking stick, he grins and says how much he enjoyed the evening: "The questions were good and hard."

Photograph by Malin LagerDr. Darin Portnoy

Photograph by Malin LagerDr. Darin Portnoy Photograph by Malin Lager

Photograph by Malin Lager Photograph by Malin Lager

Photograph by Malin Lager

from

from