Grand jury or not, the police are on trial

In Ferguson, Michael Brown lost his life — and America's police lost the benefit of the doubt

Police should realize that the law may be on their side, but public opinion changes faster than legislation

By Peter Weber

Let's give the grand jury in St. Louis County, Mo., the benefit of the doubt. The 12 never-to-be-identified men and women had no idea the case they would get when they were seated last May, three months before white Ferguson Police Officer Darren Wilson shot and killed unarmed black teenager Michael Brown Jr. on Aug. 9.

The grand jurors are "the only ones who have heard all the evidence," Bob McCulloch, St. Louis County prosecutor, said at a press conference Monday night. "The duty of the grand jury is to separate fact and fiction," he added. Barring new evidence, there's no reason to believe that the 12 jurors did anything other than carefully weigh the huge amounts of evidence and come to their best conclusion in accordance with the law.

That doesn't mean that justice was served. Legal justice and cosmic justice don't always line up neatly.

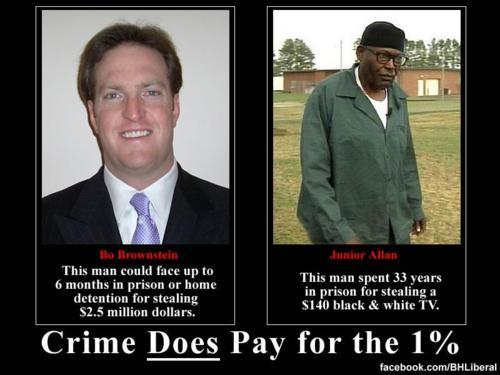

Darren Wilson will probably have to find a new career now, but Michael Brown's parents can never get a new son. Even Wilson's biggest supporters must acknowledge that stealing a box of cigarillos, walking in the middle of the street, and even stupidly punching an officer in his SUV (if Wilson's version of events is true) aren't capital crimes. Michael Brown shouldn't have died at 18 on the streets of Ferguson at the hands of a police officer.

Brown's family said in a statement after the grand jury declined to indict Wilson that they are "profoundly disappointed that the killer of our child will not face the consequence of his actions."

Preparing for the grand jury decision, Michael Brown Sr. released a video last Thursday with thevery human plea, "No matter what the grand jury decides, I do not want my son's death to be in vain." He added that he wants the loss of his son "to lead to incredible change, positive change," and in the family's statement on Monday, they suggested one change to work toward: "Join with us in our campaign to ensure that every police officer working the streets in the country wears a body camera."

The Brown family's pleas for peaceful protests and respect for private property weren't heeded, but after Michael Brown's untimely death, their call for increased use of body cameras shouldn't fall on deaf ears. Because while Darren Wilson won't go to jail, his lethal confrontation with the unarmed teen has made America pay attention to the uncertain number of police homicides, usually unpunished or penalized with a slap on the wrist. This is a problem the police need to confront.

One rallying cry for the protests that spanned the U.S. from coast to coast on Monday night is "Black lives matter." But while police shoot young black men at higher rates than white ones, according to the best numbers available, this isn't just an issue of white cops killing black men. Thanks to Brown's death, for example, conservatives were briefly (and justifiably) outraged that a non-white Salt Lake City police officer, Bron Cruz, killed a white 20-year-old male named Dillon Taylor, two days after Brown was shot dead.

In the three and a half months since Brown's death, a number of other police shootings that would have been considered local stories previously became national news, most recently the homicideSunday of a black 12-year-old boy in Cleveland, Tamir Rice, who was shot by a police officer while playing with a somewhat realistic looking toy pistol. There are, sadly, a number of other examples.

Many of the victims, like 20-year-old John Crawford III — shot by police while holding a pellet gun in an Ohio Walmart in August — are black; several others, like Kajieme Powell in St. Louis andTanisha Anderson in Cleveland, were mentally ill. In some lucky instances, like Levar Jones' in South Carolina — he was shot in September by a state trooper for trying to retrieve his driver's license, as requested — the injuries weren't fatal.

In all these police shootings there are extenuating circumstances — usually the officers truly (if incorrectly) believed they were in danger. But whereas previous cases of police homicide were considered tragic, if outrageous, outliers — think the 1999 shooting of Amadou Diallo in New York — since Brown's death the big takeaway is that unnecessary police shootings are tragically routine.

And it's not just police homicides that have come under scrutiny. Since the Ferguson protests in August, people have started noticing the troubling militarization of police departments, even in small-town America. And police practices that have nothing to do with Brown's death, like apparent abuse of civil forfeiture laws, have also received unprecedented scrutiny.

Civil libertarians and civil rights advocates have been railing against abuse of police force for years. Now, it seems, America is paying attention.

As FiveThirtyEight's Ben Casselman notes, the Ferguson grand jury's decision to not send Wilson to court is pretty typical. "Grand juries nearly always decide to indict," he writes. "Cases involving police shootings, however, appear to be an exception."

The difference this time is that America is watching.

Officer Darren Wilson and his colleagues have the law on their side. After all, "we strap guns on them and say, 'Go out there and put yourself in danger,'" notes CNN legal analyst Mark O'Mara. But police also need public trust — and communities need to be able to trust their designated peace officers.

The legacy of Michael Brown's death needn't be the erosion of public trust in the police, though. If more police start making their officers wear lapel cameras, like Brown's family is suggesting, it might actually be good for everyone. The Salt Lake City police have started putting cameras on beat cops, for example — and in the case of Dillon Taylor, the footage largely corroborated the police's side of the story. Video evidence is worth 1,000 witnesses; trust is priceless.

Peter Weber is a senior editor at TheWeek.com, and has handled the editorial night shift since 2008. A graduate of Northwestern University, Peter has worked at Facts on File and The New York Times Magazine. He speaks Spanish and Italian, and plays in an Austin rock band.

(

( (

(

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2478224/Screen_Shot_2014-11-21_at_9.53.24_AM.0.png)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2478226/Screen_Shot_2014-11-21_at_9.53.39_AM.0.png)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2495742/table-finalfinalup4.0.png)