![]()

Plato

***

Plato: Political Philosophy

Plato (c. 427-347 B.C.E.) developed such distinct areas of philosophy as epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aesthetics. His deep influence on Western philosophy is asserted in the famous remark of Alfred North Whitehead: “the safest characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.” He was also the prototypical political philosopher whose ideas had a profound impact on subsequent political theory. His greatest impact was Aristotle, but he influenced Western political thought in many ways. The Academy, the school he founded in 385 B.C.E., became the model for other schools of higher learning and later for European universities.The philosophy of Plato is marked by the usage of dialectic, a method of discussion involving ever more profound insights into the nature of reality, and by cognitive optimism, a belief in the capacity of the human mind to attain the truth and to use this truth for the rational and virtuous ordering of human affairs. Plato believes that conflicting interests of different parts of society can be harmonized. The best, rational and righteous, political order, which he proposes, leads to a harmonious unity of society and allows each of its parts to flourish, but not at the expense of others. The theoretical design and practical implementation of such order, he argues, are impossible without virtue.

Table of Contents

- Life - from Politics to Philosophy

- The Threefold Task of Political Philosophy

- The Quest for Justice in The Republic

- The Best Political Order

- The Government of Philosopher Rulers

- Politics and the Soul

- Plato’s Achievement

![]()

1. Life - from Politics to Philosophy

Plato was born in Athens in c. 427 B.C.E. Until his mid-twenties, Athens was involved in a long and disastrous military conflict with Sparta, known as the Peloponnesian War. Coming from a distinguished family - on his father’s side descending from Codrus, one of the early kings of Athens, and on his mother’s side from Solon, the prominent reformer of the Athenian constitution - he was naturally destined to take an active role in political life. But this never happened. Although cherishing the hope of assuming a significant place in his political community, he found himself continually thwarted. As he relates in his autobiographical Seventh Letter, he could not identify himself with any of the contending political parties or the succession of corrupt regimes, each of which brought Athens to further decline (324b-326a). He was a pupil of Socrates, whom he considered the most just man of his time, and who, although did not leave any writings behind, exerted a large influence on philosophy. It was Socrates who, in Cicero’s words, “called down philosophy from the skies.” The pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology and ontology; Socrates’ concerns, in contrast, were almost exclusively moral and political issues. In 399 when a democratic court voted by a large majority of its five hundred and one jurors for Socrates’ execution on an unjust charge of impiety, Plato came to the conclusion that all existing governments were bad and almost beyond redemption. “The human race will have no respite from evils until those who are really philosophers acquire political power or until, through some divine dispensation, those who rule and have political authority in the cities become real philosophers” (326a-326b).

It was perhaps because of this opinion that he retreated to his Academy and to Sicily for implementing his ideas. He visited Syracuse first in 387, then in 367, and again in 362-361, with the general purpose to moderate the Sicilian tyrants with philosophical education and to establish a model political rule. But this adventure with practical politics ended in failure, and Plato went back to Athens. His Academy, which provided a base for succeeding generations of Platonic philosophers until its final closure in C.E. 529, became the most famous teaching institution of the Hellenistic world. Mathematics, rhetoric, astronomy, dialectics, and other subjects, all seen as necessary for the education of philosophers and statesmen, were studied there. Some of Plato’s pupils later became leaders, mentors, and constitutional advisers in Greek city-states. His most renowned pupil was Aristotle. Plato died in c. 347 B.C.E. During his lifetime, Athens turned away from her military and imperial ambitions and became the intellectual center of Greece. She gave host to all the four major Greek philosophical schools founded in the course of the fourth century: Plato’s Academy, Aristotle’s Lyceum, and the Epicurean and Stoic schools.

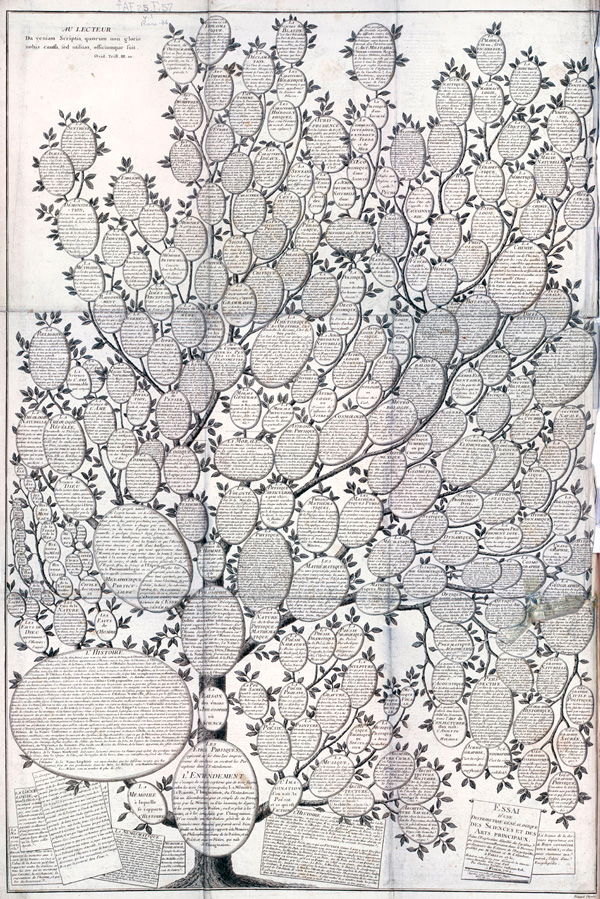

2. The Threefold Task of Political Philosophy

Although the Republic, the Statesman, the Laws and a few shorter dialogues are considered to be the only strictly political dialogues of Plato, it can be argued that political philosophy was the area of his greatest concern. In the English-speaking world, under the influence of twentieth century analytic philosophy, the main task of political philosophy today is still often seen as conceptual analysis: the clarification of political concepts. To understand what this means, it may be useful to think of concepts as the uses of words. When we use general words, such as “table,” “chair,” “pen,” or political terms, such as “state,” “power,” “democracy,” or “freedom,” by applying them to different things, we understand them in a certain way, and hence assign to them certain meanings. Conceptual analysis then is a mental clearance, the clarification of a concept in its meaning. As such it has a long tradition and is first introduced in Platonic dialogues. Although the results are mostly inconclusive, in “early” dialogues especially, Socrates tries to define and clarify various concepts. However, in contrast to what it is for some analytic philosophers, for Plato conceptual analysis is not an end to itself, but a preliminary step. The next step is critical evaluation of beliefs, deciding which one of the incompatible ideas is correct and which one is wrong. For Plato, making decisions about the right political order are, along with the choice between peace and war, the most important choices one can make in politics. Such decisions cannot be left solely to public opinion, he believes, which in many cases does not have enough foresight and gets its lessons only post factum from disasters recorded in history. In his political philosophy, the clarification of concepts is thus a preliminary step in evaluating beliefs, and right beliefs in turn lead to an answer to the question of the best political order. The movement from conceptual analysis, through evaluation of beliefs, to the best political order can clearly be seen in the structure of Plato’s Republic.

3. The Quest for Justice in The Republic

One of the most fundamental ethical and political concepts is justice. It is a complex and ambiguous concept. It may refer to individual virtue, the order of society, as well as individual rights in contrast to the claims of the general social order. In Book I of the Republic, Socrates and his interlocutors discuss the meaning of justice. Four definitions that report how the word “justice” (dikaiosune) is actually used, are offered. The old man of means Cephalus suggests the first definition. Justice is “speaking the truth and repaying what one has borrowed” (331d). Yet this definition, which is based on traditional moral custom and relates justice to honesty and goodness; i.e. paying one’s debts, speaking the truth, loving one’s country, having good manners, showing proper respect for the gods, and so on, is found to be inadequate. It cannot withstand the challenge of new times and the power of critical thinking. Socrates refutes it by presenting a counterexample. If we tacitly agree that justice is related to goodness, to return a weapon that was borrowed from someone who, although once sane, has turned into a madman does not seem to be just but involves a danger of harm to both sides. Cephalus’ son Polemarchus, who continues the discussion after his father leaves to offer a sacrifice, gives his opinion that the poet Simonides was correct in saying that it was just “to render to each his due” (331e). He explains this statement by defining justice as “treating friends well and enemies badly” (332d). Under the pressure of Socrates’ objections that one may be mistaken in judging others and thus harm good people, Polemarchus modifies his definition to say that justice is “to treat well a friend who is good and to harm an enemy who is bad” (335a). However, when Socrates finally objects that it cannot be just to harm anyone, because justice cannot produce injustice, Polemarchus is completely confused. He agrees with Socrates that justice, which both sides tacitly agree relates to goodness, cannot produce any harm, which can only be caused by injustice. Like his father, he withdraws from the dialogue. The careful reader will note that Socrates does not reject the definition of justice implied in the saying of Simonides, who is called a wise man, namely, that “justice is rendering to each what befits him” (332b), but only its explication given by Polemarchus. This definition is, nevertheless, found unclear.

The first part of Book I of the Republic ends in a negative way, with parties agreeing that none of the definitions provided stands up to examination and that the original question “What is justice?” is more difficult to answer than it seemed to be at the outset. This negative outcome can be seen as a linguistic and philosophical therapy. Firstly, although Socrates’ objections to given definitions can be challenged, it is shown, as it stands, that popular opinions about justice involve inconsistencies. They are inconsistent with other opinions held to be true. The reportive definitions based on everyday usage of the word “justice” help us perhaps to understand partially what justice means, but fail to provide a complete account of what is justice. These definitions have to be supplied by a definition that will assist clarity and establish the meaning of justice. However, to propose such an adequate definition one has to know what justice really is. The way people define a given word is largely determined by the beliefs which they hold about the thing referred to by this word. A definition that is merely arbitrary or either too narrow or too broad, based on a false belief about justice, does not give the possibility of communication. Platonic dialogues are expressions of the ultimate communication that can take place between humans; and true communication is likely to take place only if individuals can share meanings of the words they use. Communication based on false beliefs, such as statements of ideology, is still possible, but seems limited, dividing people into factions, and, as history teaches us, can finally lead only to confusion. The definition of justice as “treating friends well and enemies badly” is for Plato not only inadequate because it is too narrow, but also wrong because it is based on a mistaken belief of what justice is, namely, on the belief grounded in factionalism, which Socrates does not associate with the wise ones but with tyrants (336a). Therefore, in the Republic, as well as in other Platonic dialogues, there is a relationship between conceptual analysis and critical evaluation of beliefs. The goals of these conversations are not merely linguistic, to arrive at an adequate verbal definition, but also substantial, to arrive at a right belief. The question “what is justice” is not only about linguistic usage of the word “justice,” but primarily about the thing to which the word refers. The focus of the second part of Book I is no longer clarification of concepts, but evaluation of beliefs.

In Platonic dialogues, rather than telling them what they have to think, Socrates is often getting his interlocutors to tell him what they think. The next stage of the discussion of the meaning of justice is taken over by Thrasymachus, a sophist, who violently and impatiently bursts into the dialogue. In the fifth and fourth century B.C.E., the sophists were paid teachers of rhetoric and other practical skills, mostly non-Athenians, offering courses of instruction and claiming to be best qualified to prepare young men for success in public life. Plato describes the sophists as itinerant individuals, known for their rhetorical abilities, who reject religious beliefs and traditional morality, and he contrasts them with Socrates, who as a teacher would refuse to accept payment and instead of teaching skills would commit himself to a disinterested inquiry into what is true and just. In a contemptuous manner, Thrasymachus asks Socrates to stop talking nonsense and look into the facts. As a clever man of affairs, he gives an answer to the question of “what is justice” by deriving justice from the city’s configuration of power and making it relative to the interests of the dominant social or political group. “Justice is nothing else than the interest of the stronger” (338c). Now, by contrast to what some commentators say, the statement that Thrasymachus offers as an answer to Socrates’ question about justice is not a definition. The careful reader will notice that Thrasymachus identifies justice with either maintenance or observance of law. His statement is an expression of his belief that, in the world imperfect as it is, the ruling element in the city, or as we would say today the dominant political or social group, institutes laws and governs for its own benefit (338d). The democrats make laws in support of democracy; the aristocrats make laws that support the government of the well-born; the propertied make laws that protect their status and keep their businesses going; and so on. This belief implies, firstly, that justice is not a universal moral value but a notion relative to expediency of the dominant status quo group; secondly, that justice is in the exclusive interest of the dominant group; thirdly, that justice is used as a means of oppression and thus is harmful to the powerless; fourthly, that there is neither any common good nor harmony of interests between those who are in a position of power and those who are not. All there is, is a domination by the powerful and privileged over the powerless. The moral language of justice is used merely instrumentally to conceal the interests of the dominant group and to make these interests appear universal. The powerful “declare what they have made - what is to their own advantage - to be just” (338e). The arrogance with which Thrasymachus makes his statements suggests that he strongly believes that to hold a different view from his own would be to mislead oneself about the world as it is.

After presenting his statement, Thrasymachus intends to leave as if he believed that what he said was so compelling that no further debate about justice was ever possible (344d). In the Republic he exemplifies the power of a dogma. Indeed he presents Socrates with a powerful challenge. Yet, whether or not what he said sounds attractive to anyone, Socrates is not convinced by the statement of his beliefs. Beliefs shape our lives as individuals, nations, ages, and civilizations. Should we really believe that “justice [obeying laws] is really the good of another, the advantage of the stronger and the ruler, harmful to the one who obeys, while injustice [disobeying laws] is in one’s own advantage” (343c)? The discussion between Socrates and his interlocutors is no longer about the meaning of “justice.” It is about fundamental beliefs and “concerns no ordinary topic but the way we ought to live” (352d). Although in Book I Socrates finally succeeds in showing Thrasymachus that his position is self-contradictory and Thrasymachus withdraws from the dialogue, perhaps not fully convinced, yet red-faced, in Book II Thrasymachus’ argument is taken over by two young intellectuals, Plato’s brothers, Glaucon and Adeimantus, who for the sake of curiosity and a playful intellectual exercise push it to the limit (358c-366d). Thrasymachus withdraws, but his statement: moral skepticism and relativism, predominance of power in human relations, and non-existence of the harmony of interests, hovers over the Western mind. It takes whole generations of thinkers to struggle with Thrasymachus’ beliefs, and the debate still continues. It takes the whole remainder of the Republic to present an argument in defense of justice as a universal value and the foundation of the best political order.

4. The Best Political Order

Although large parts of the Republic are devoted to the description of an ideal state ruled by philosophers and its subsequent decline, the chief theme of the dialogue is justice. It is fairly clear that Plato does not introduce his fantastical political innovation, which Socrates describes as a city in speech, a model in heaven, for the purpose of practical implementation (592a-b). The vision of the ideal state is used rather to illustrate the main thesis of the dialogue that justice, understood traditionally as virtue and related to goodness, is the foundation of a good political order, and as such is in everyone’s interest. Justice, if rightly understood, Plato argues, is not to the exclusive advantage of any of the city’s factions, but is concerned with the common good of the whole political community, and is to the advantage of everyone. It provides the city with a sense of unity, and thus, is a basic condition for its health. “Injustice causes civil war, hatred, and fighting, while justice brings friendship and a sense of common purpose” (351d). In order to understand further what justice and political order are for Plato, it is useful to compare his political philosophy with the pre-philosophical insights of Solon, who is referred to in a few dialogues. Biographical information about Plato is fairly scarce. The fact that he was related through his mother to this famous Athenian legislator, statesman and poet, regarded as one of the “Seven Sages,” may be treated as merely incidental. On the other hand, taking into consideration that in Plato’s times education would have been passed on to children informally at home, it seems highly probable that Plato was not only well acquainted with the deeds and ideas of Solon, but that these deeply influenced him.

The essence of the constitutional reform which Solon made in 593 B.C.E., over one hundred and fifty years before Plato’s birth, when he became the Athenian leader, was the restoration of righteous order, eunomia. In the early part of the sixth century Athens was disturbed by a great tension between two parties: the poor and the rich, and stood at the brink of a fierce civil war. On the one hand, because of an economic crisis, many poorer Athenians were hopelessly falling into debt, and since their loans were often secured by their own persons, thousands of them were put into serfdom. On the other hand, lured by easy profits from loans, the rich stood firmly in defense of private property and their ancient privileges. The partisan strife, which seemed inevitable, would make Athens even more weak economically and defenseless before external enemies. Appointed as a mediator in this conflict, Solon enacted laws prohibiting loans on the security of the person. He lowered the rate of interest, ordered the cancellation of all debts, and gave freedom to serfs. He acted so moderately and impartially that he became unpopular with both parties. The rich felt hurt by the reform. The poor, unable to hold excess in check, demanded a complete redistribution of landed property and the dividing of it into equal shares. Nevertheless, despite these criticisms from both sides, Solon succeeded in gaining social peace. Further, by implementing new constitutional laws, he set up a “mighty shield against both parties and did not allow either to win an unjust victory” (Aristotle, The Athenian Constitution). He introduced a system of checks and balances which would not favor any side, but took into consideration legitimate interests of all social groups. In his position, he could easily have become the tyrant over the city, but he did not seek power for himself. After he completed his reform, he left Athens in order to see whether it would stand the test of time, and returned to his country only ten years later. Even though in 561 Pisistratus seized power and became the first in a succession of Athenian tyrants, and in 461 the democratic leader Ephialtes abolished the checks upon popular sovereignty, Solon’s reform provided the ancient Greeks with a model of both political leadership and order based on impartiality and fairness. Justice for Solon is not an arithmetical equality: giving equal shares to all alike irrespective of merit, which represents the democratic concept of distributive justice, but it is equity or fairness based on difference: giving shares proportionate to the merit of those who receive them. The same ideas of political order, leadership, and justice can be found in Plato’s dialogues.

For Plato, like for Solon, the starting point for the inquiry about the best political order is the fact of social diversity and conflicting interests, which involve the danger of civil strife. The political community consists of different parts or social classes, such as the noble, the rich, and the poor, each representing different values, interests, and claims to rule. This gives rise to the controversy of who should rule the community, and what is the best political system. In both the Republic and the Laws, Plato asserts not only that factionalism and civil war are the greatest dangers to the city, more dangerous even than war against external enemies, but also that peace obtained by the victory of one part and the destruction of its rivals is not to be preferred to social peace obtained through the friendship and cooperation of all the city’s parts (Republic 462a-b, Laws 628a-b). Peace for Plato is, unlike for Marxists and other radical thinkers, not a status quo notion, related to the interest of the privileged group, but a value that most people usually desire. He does not stand for war and the victory of one class, but for peace in social diversity. “The best is neither war nor faction - they are things we should pray to be spared from - but peace and mutual good will” (628c). Building on the pre-philosophical insights of Solon and his concept of balancing conflicting interests, in both the Republic and the Laws, Plato offers two different solutions to the same problem of social peace based on the equilibrium and harmonious union of different social classes. If in the Republic it is the main function of the political leadership of philosopher-rulers to make the civil strife cease, in the Laws this mediating function is taken over by laws. The best political order for Plato is that which promotes social peace in the environment of cooperation and friendship among different social groups, each benefiting from and each adding to the common good. The best form of government, which he advances in the Republic, is a philosophical aristocracy or monarchy, but that which he proposes in his last dialogue the Laws is a traditional polity: the mixed or composite constitution that reconciles different partisan interests and includes aristocratic, oligarchic, and democratic elements.

5. The Government of Philosopher Rulers

It is generally believed today that democracy, “government of the people by the people and for the people,” is the best and only fully justifiable political system. The distinct features of democracy are freedom and equality. Democracy can be described as the rule of the free people who govern themselves, either directly or though their representatives, in their own interest. Why does Plato not consider democracy the best form of government? In the Republic he criticizes the direct and unchecked democracy of his time precisely because of its leading features (557a-564a). Firstly, although freedom is for Plato a true value, democracy involves the danger of excessive freedom, of doing as one likes, which leads to anarchy. Secondly, equality, related to the belief that everyone has the right and equal capacity to rule, brings to politics all kinds of power-seeking individuals, motivated by personal gain rather than public good. Democracy is thus highly corruptible. It opens gates to demagogues, potential dictators, and can thus lead to tyranny. Hence, although it may not be applicable to modern liberal democracies, Plato’s main charge against the democracy he knows from the ancient Greek political practice is that it is unstable, leading from anarchy to tyranny, and that it lacks leaders with proper skill and morals. Democracy depends on chance and must be mixed with competent leadership (501b). Without able and virtuous leaders, such as Solon or Pericles, who come and go by chance, it is not a good form of government. But even Pericles, who as Socrates says made people “wilder” rather than more virtuous, is considered not to be the best leader (Gorgias, 516c). If ruling a state is a craft, indeed statecraft, Plato argues, then politics needs expert rulers, and they cannot come to it merely by accident, but must be carefully selected and prepared in the course of extensive training. Making political decisions requires good judgment. Politics needs competence, at least in the form of today’s civil servants. Who then should the experts be and why? Why does Plato in the Republic decide to hand the steering wheel of the state to philosophers?

In spite of the idealism with which he is usually associated, Plato is not politically naive. He does not idealize, but is deeply pessimistic about human beings. Most people, corrupted as they are, are for him fundamentally irrational, driven by their appetites, egoistic passions, and informed by false beliefs. If they choose to be just and obey laws, it is only because they lack the power to act criminally and are afraid of punishment (Republic, 359a). Nevertheless, human beings are not vicious by nature. They are social animals, incapable of living alone (369a-b). Living in communities and exchanging products of their labor is natural for them, so that they have capacities for rationality and goodness. Plato, as later Rousseau, believes that once political society is properly ordered, it can contribute to the restoration of morals. A good political order, good education and upbringing can produce “good natures; and [these] useful natures, who are in turn well educated, grow up even better than their predecessors” (424a). Hence, there are in Plato such elements of the idealistic or liberal world view as the belief in education and progress, and a hope for a better future. The quality of human life can be improved if people learn to be rational and understand that their real interests lie in harmonious cooperation with one another, and not in war or partisan strife. However, unlike Rousseau, Plato does not see the best social and political order in a democratic republic. Opinions overcome truth in everyday life. Peoples’ lives and the lives of communities are shaped by the prevailing beliefs. If philosophers are those who can distinguish between true and false beliefs, who love knowledge and are motivated by the common good, and finally if they are not only master-theoreticians, but also the master-practitioners who can heal the ills of their society, then they, and not democratically elected representatives, must be chosen as leaders and educators of the political community and guide it to proper ends. They are required to counteract the destabilizing effects of false beliefs on society. Are philosophers incorruptible? In the ideal city there are provisions to minimize possible corruption, even among the good-loving philosophers. They can neither enjoy private property nor family life. Although they are the rulers, they receive only a modest remuneration from the state, dine in common dining halls, and have wives and children in common. These provisions are necessary, Plato believes, because if the philosopher-rulers were to acquire private land, luxurious homes, and money themselves, they would soon become hostile masters of other citizens rather than their leaders and allies (417a-b). The ideal city becomes a bad one, described as timocracy, precisely when the philosophers neglect music and physical exercise, and begin to gather wealth (547b).

To be sure, Plato’s philosophers, among whom he includes both men and women, are not those who can usually be found today in departments of philosophy and who are described as the “prisoners who take refuge in a temple” (495a). Initially chosen from among the brightest, most stable, and most courageous children, they go through a sophisticated and prolonged educational training which begins with gymnastics, music and mathematics, and ends with dialectic, military service and practical city management. They have superior theoretical knowledge, including the knowledge of the just, noble, good and advantageous, but are not inferior to others in practical matters as well (484d, 539e). Being in the final stage of their education illuminated by the idea of the good, they are those who can see beyond changing empirical phenomena and reflect on such timeless values as justice, beauty, truth, and moderation (501b, 517b). Goodness is not merely a theoretical idea for them, but the ultimate state of their mind. If the life of the philosopher-rulers is not of private property, family or wealth, nor even of honor, and if the intellectual life itself seems so attractive, why should they then agree to rule? Plato’s answer is in a sense a negative one. Philosophical life, based on contemplative leisure and the pleasure of learning, is indeed better and happier than that of ruling the state (519d). However, the underlying idea is not to make any social class in the city the victorious one and make it thus happy, but “to spread happiness throughout the city by bringing the citizens into harmony with each other ... and by making them share with each other the benefits that each class can confer on the community” (519e). Plato assumes that a city in which the rulers do not govern out of desire for private gain, but are least motivated by personal ambition, is governed in the way which is the finest and freest from civil strife (520d). Philosophers will rule not only because they will be best prepared for this, but also because if they do not, the city will no longer be well governed and may fall prey to economic decline, factionalism, and civil war. They will approach ruling not as something really enjoyable, but as something necessary (347c-d).

Objections against the government of philosopher-rulers can be made. Firstly, because of the restrictions concerning family and private property, Plato is often accused of totalitarianism. However, Plato’s political vision differs from a totalitarian state in a number of important aspects. Especially in the Laws he makes clear that freedom is one of the main values of society (701d). Other values for which Plato stands include justice, friendship, wisdom, courage, and moderation, and not factionalism or terror that can be associated with a totalitarian state. The restrictions which he proposes are placed on the governors, rather than on the governed. Secondly, one can argue that there may obviously be a danger in the self-professed claim to rule of the philosophers. Individuals may imagine themselves to be best qualified to govern a country, but in fact they may lose contact with political realities and not be good leaders at all. If philosopher-rulers did not have real knowledge of their city, they would be deprived of the essential credential that is required to make their rule legitimate, namely, that they alone know how best to govern. Indeed, at the end of Book VII of the Republicwhere philosophers’ education is discussed, Socrates says: “I forgot that we were only playing, and so I spoke too vehemently” (536b), as if to imply that objections can be made to philosophical rule. As in a few other places in the dialogue, Plato throws his political innovation open to doubt. However, in Plato’s view, philosopher-rulers do not derive their authority solely from their expert knowledge, but also from their love of the city as a whole and their impartiality and fairness. Their political authority is not only rational but also substantially moral, based on the consent of the governed. They regard justice as the most important and most essential thing (540e). Even if particular political solutions presented in the Republic may be open to questioning, what seems to stand firm is the basic idea that underlies philosophers’ governance and that can be traced back to Solon: the idea of fairness based on difference as the basis of the righteous political order. A political order based on fairness leads to friendship and cooperation among different parts of the city.

For Plato, as for Solon, government exists for the benefit of all citizens and all social classes, and must mediate between potentially conflicting interests. Such a mediating force is exercised in the ideal city of the

Republic by the philosopher-rulers. They are the guarantors of the political order that is encapsulated in the norm that regulates just relations of persons and classes within the city and is expressed by the phrase: “doing one’s own work and not meddling with what isn’t one’s own” (433a-b). If justice is related to equality, the notion of equality is indeed preserved in Plato’s view of justice expressed by this norm as the impartial, equal treatment of all citizens and social groups. It is not the case that Plato knew that his justice meant equality but really made inequality, as

Karl Popper (one of his major critics) believed. In the ideal city all persons and social groups are given equal opportunities to be happy, that is, to pursue happiness, but not at the expense of others. Their particular individual, group or class happiness is limited by the need of the happiness for all. The happiness of the whole city is not for Plato the happiness of an abstract unity called the polis, or the happiness of the greatest number, but rather the happiness of all citizens derived from a peaceful, harmonious, and cooperative union of different social classes. According to the traditional definition of justice by Simonides from Book I, which is reinterpreted in Book IV, as “doing one’s own work,” each social class receives its proper due in the distribution of benefits and burdens. The philosopher-rulers enjoy respect and contemplative leisure, but not wealth or honors; the guardian class, the second class in the city, military honors, but not leisure or wealth; and the producer class, family life, wealth, and freedom of enterprise, but not honors or rule. Then, the producers supply the city with goods; the guardians, defend it; and the philosophers, attuned to virtue and illuminated by goodness, rule it impartially for the common benefit of all citizens. The three different social classes engage in mutually beneficial enterprise, by which the interests of all are best served. Social and economic differences, i.e. departures from equality, bring about benefits to people in all social positions, and therefore, are justified. In the Platonic vision of the

Republic, all social classes get to perform what they are best fit to do and are unified into a single community by mutual interests. In this sense, although each are different, they are all friends.

6. Politics and the Soul

It can be contended that the whole argument of the Republic is made in response to the denial of justice as a universal moral value expressed in Thrasymachus’ statement: “Justice is nothing else than the interest of the stronger.” Moral relativism, the denial of the harmony of interests, and other problems posed by this statement are a real challenge for Plato for whom justice is not merely a notion relative to the existing laws instituted by the victorious factions in power. In the Laws a similar statement is made again (714c), and it is interpreted as the right of the strong, the winner in a political battle (715a). By such interpretation, morality is denied and the right to govern, like in the “Melian Dialogue” of Thucydides, is equated simply with might. The decisions about morals and justice which we make are for Plato “no trifle, but the foremost thing” (714b). The answer to the question of what is right and what is wrong can entirely determine our way of life, as individuals and communities. If Plato’s argument about justice presented in both the Republic and the Laws can be summarized in just one sentence, the sentence will say: “Justice is neither the right of the strong nor the advantage of the stronger, but the right of the best and the advantage of the whole community.” The best, as explained in the Republic, are the expert philosophical rulers. They, the wise and virtuous, free from faction and guided by the idea of the common good, should rule for the common benefit of the whole community, so that the city will not be internally divided by strife, but one in friendship (Republic, 462a-b). Then, in theLaws, the reign of the best individuals is replaced by the reign of the finest laws instituted by a judicious legislator (715c-d). Throughout this dialogue Plato’s guiding principle is that the good society is a harmonious union of different social elements that represent two key values: wisdom and freedom (701d). The best laws assure that all the city’s parts: the democratic, the oligarchic, and the aristocratic, are represented in political institutions: the popular Assembly, the elected Council, and the Higher Council, and thus each social class receives its due expression. Still, a democratic skeptic can feel dissatisfied with Plato’s proposal to grant the right to rule to the best, either individuals or laws, even on the basis of tacit consent of the governed. The skeptic may believe that every adult is capable of exercising the power of self-direction, and should be given the opportunity to do so. He will be prepared to pay the costs of eventual mistakes and to endure an occasional civil unrest or even a limited war rather than be directed by anyone who may claim superior wisdom. Why then should Plato’s best constitution be preferable to democracy? In order to fully explain the Platonic political vision, the meaning of “the best” should be further clarified.

In the short dialogue Alcibiades I, little studied today and thought by some scholars as not genuine, though held in great esteem by the Platonists of antiquity, Socrates speaks with Alcibiades. The subject of their conversation is politics. Frequently referred to by Thucydides in the History of the Peloponnesian War, Alcibiades, the future leader of Athens, highly intelligent and ambitious, largely responsible for the Athenian invasion of Sicily, is at the time of conversation barely twenty years old. The young, handsome, and well-born Alcibiades of the dialogue is about to begin his political career and to address the Assembly for the first time (105a-b). He plans to advise the Athenians on the subject of peace and war, or some other important affair (107d). His ambitions are indeed extraordinary. He does not want just to display his worth before the people of Athens and become their leader, but to rule over Europe and Asia as well (105c). His dreams resemble that of the future Alexander the Great. His claim to rule is that he is the best. However, upon Socrates’ scrutiny, it becomes apparent that young Alcibiades knows neither what is just, nor what is advantageous, nor what is good, nor what is noble, beyond what he has learned from the crowd (110d-e, 117a). His world-view is based on unexamined opinions. He appears to be the worst type of ignorant person who pretends that he knows something but does not. Such ignorance in politics is the cause of mistakes and evils (118a). What is implied in the dialogue is that noble birth, beautiful looks, and even intelligence and power, without knowledge, do not give the title to rule. Ignorance, the condition of Alcibiades, is also the condition of the great majority of the people (118b-c). Nevertheless, Socrates promises to guide Alcibiades, so that he becomes excellent and renowned among the Greeks (124b-c). In the course of further conversation, it turns out that one who is truly the best does not only have knowledge of political things, rather than an opinion about them, but also knows one’s own self and is a beautiful soul. He or she is perfect in virtue. The riches of the world can be entrusted only to those who “take trouble over” themselves (128d), who look “toward what is divine and bright” (134d), and who following the supreme soul, God, the finest mirror of their own image (133c), strive to be as beautiful and wealthy in their souls as possible (123e, 131d). The best government can be founded only on beautiful and well-ordered souls.

In a few dialogues, such as

Phaedo, the

Republic,

Phaedrus,

Timaeus, and the

Laws, Plato introduces his doctrine of the immortality of the soul. His ultimate answer to the question “Who am I?” is not an “egoistic animal” or an “independent variable,” as the twentieth century behavioral researcher blatantly might say, but an “immortal soul, corrupted by vice and purified by virtue, of whom the body is only an instrument” (129a-130c). Expert political knowledge for him should include not only knowledge of things out there, but also knowledge of oneself. This is because whoever is ignorant of himself will also be ignorant of others and of political things, and, therefore, will never be an expert politician (133e). Those who are ignorant will go wrong, moving from one misery to another (134a). For them history will be a tough teacher, but as long they do not recognize themselves and practice virtue, they will learn nothing. Plato’s good society is impossible without transcendence, without a link to the perfect being who is God, the true measure of all things. It is also impossible without an ongoing philosophical reflection on whom we truly are. Therefore, democracy would not be a good form of government for him unless, as it is proposed in the

Laws, the element of freedom is mixed with the element of wisdom, which includes ultimate knowledge of the self. Unmixed and unchecked democracy, marked by the general permissiveness that spurs vices, makes people impious, and lets them forget about their true self, is only be the second worst in the rank of flawed regimes after tyranny headed by a vicious individual. This does not mean that Plato would support a theocratic government based on shallow religiosity and religious hypocrisy. There is no evidence for this. Freedom of speech, forming opinions and expressing them, which may be denied in theocracy, is a true value for Plato, along with wisdom. It is the basic requirement for philosophy. In shallow religiosity, like in

atheism, there is ignorance and no knowledge of the self either. In Book II of the

Republic, Plato criticizes the popular religious beliefs of the Athenians, who under the influence of Homer and Hesiod attribute vices to the gods and heroes (377d-383c). He tries to show that God is the perfect being, the purest and brightest, always the same, immortal and true, to whom we should look in order to know ourselves and become pure and virtuous (585b-e). God, and not human beings, is the measure of political order (

Laws, 716c).

7. Plato’s Achievement

Plato’s greatest achievement may be seen firstly in that he, in opposing the sophists, offered to decadent Athens, which had lost faith in her old religion, traditions, and customs, a means by which civilization and the city’s health could be restored: the recovery of order in both the polis and the soul.

The best, rational and righteous political order leads to the harmonious unity of a society and allows all the city’s parts to pursue happiness but not at the expense of others. The characteristics of a good political society, of which most people can say “it is mine” (462c), are described in the Republic by four virtues: justice, wisdom, moderation, and courage. Justice is the equity or fairness that grants each social group its due and ensures that each “does one’s own work” (433a). The three other virtues describe qualities of different social groups. Wisdom, which can be understood as the knowledge of the whole, including both knowledge of the self and political prudence, is the quality of the leadership (428e-429a). Courage is not merely military courage but primarily civic courage: the ability to preserve the right, law-inspired belief, and stand in defense of such values as friendship and freedom on which a good society is founded. It is the primary quality of the guardians (430b). Finally, moderation, a sense of the limits that bring peace and happiness to all, is the quality of all social classes. It expresses the mutual consent of both the governed and the rulers as to who should rule (431d-432a). The four virtues of the good society describe also the soul of a well-ordered individual. Its rational part, whose quality is wisdom, nurtured by fine words and learning, should together with the emotional or spirited part, cultivated by music and rhythm, rule over the volitional or appetitive part (442a). Under the leadership of the intellect, the soul must free itself from greed, lust, and other degrading vices, and direct itself to the divine. The liberation of the soul from vice is for Plato the ultimate task of humans on earth. Nobody can be wicked and happy (580a-c). Only a spiritually liberated individual, whose soul is beautiful and well ordered, can experience true happiness. Only a country ordered according to the principles of virtue can claim to have the best system of government.

Plato’s critique of democracy may be considered by modern readers as not applicable to liberal democracy today. Liberal democracies are not only founded on considerations of freedom and equality, but also include other elements, such as the rule of law, multiparty systems, periodic elections, and a professional civil service. Organized along the principle of separation of powers, today’s Western democracy resembles more a revised version of mixed government, with a degree of moderation and competence, rather than the highly unstable and unchecked Athenian democracy of the fourth and fifth century B.C.E., in which all governmental policies were directly determined by the often changing moods of the people. However, what still seems to be relevant in Plato’s political philosophy is that he reminds us of the moral and spiritual dimension of political life. He believes that virtue is the lifeblood of any good society.

Moved by extreme ambitions, the Athenians, like the mythological Atlantians described in the dialogue Critias, became infected by “wicked coveting and the pride of power” (121b). Like the drunken Alcibiades from theSymposium, who would swap “bronze for gold” and thus prove that he did not understand the Socratic teaching, they chose the “semblance of beauty,” the shining appearance of power and material wealth, rather than the “thing itself,” the being of perfection (Symposium, 218e). “To the seen eye they now began to seem foul, for they were losing the fairest bloom from their precious treasure, but to such who could not see the truly happy life, they would appear fair and blessed” (Critias, 121b). They were losing their virtuous souls, their virtue by which they could prove themselves to be worthy of preservation as a great nation. Racked by the selfish passions of greed and envy, they forfeited their conception of the right order. Their benevolence, the desire to do good, ceased. “Man and city are alike,” Plato claims (Republic, 577d). Humans without souls are hollow. Cities without virtue are rotten. To those who cannot see clearly they may look glorious but what appears bright is only exterior. To see clearly what is visible, the political world out there, Plato argues, one has first to perceive what is invisible but intelligible, the soul. One has to know oneself. Humans are immortal souls, he claims, and not just independent variables. They are often egoistic, but the divine element in them makes them more than mere animals. Friendship, freedom, justice, wisdom, courage, and moderation are the key values that define a good society based on virtue, which must be guarded against vice, war, and factionalism. To enjoy true happiness, humans must remain virtuous and remember God, the perfect being.

Plato’s achievement as a political philosopher may be seen in that he believed that there could be a body of knowledge whose attainment would make it possible to heal political problems, such as factionalism and the corruption of morals, which can bring a city to a decline. The doctrine of the harmony of interests, fairness as the basis of the best political order, the mixed constitution, the rule of law, the distinction between good and deviated forms of government, practical wisdom as the quality of good leadership, and the importance of virtue and transcendence for politics are the political ideas that can rightly be associated with Plato. They have profoundly influenced subsequent political thinkers.

Author Information

Beyond having written one of the finest books on writing ever published, Anne Lamott embraces language and life with equal zest, squeezing from the intersection wisdom of the most soul-stretching kind. Small Victories: Spotting Improbable Moments of Grace (public library | IndieBound) shines a sidewise gleam at Lamott's much-loved meditations onwhy perfectionism kills creativity and how we keep ourselves small by people-pleasing to explore the boundless blessings of our ample imperfections, from which our most expansive and transcendent humanity springs.

Beyond having written one of the finest books on writing ever published, Anne Lamott embraces language and life with equal zest, squeezing from the intersection wisdom of the most soul-stretching kind. Small Victories: Spotting Improbable Moments of Grace (public library | IndieBound) shines a sidewise gleam at Lamott's much-loved meditations onwhy perfectionism kills creativity and how we keep ourselves small by people-pleasing to explore the boundless blessings of our ample imperfections, from which our most expansive and transcendent humanity springs.The welcome book would have taught us that power and signs of status can't save us, that welcome – both offering and receiving – is our source of safety. Various chapters and verses of this book would remind us that we are wanted and even occasionally delighted in, despite the unfortunate truth that we are greedy-grabby, self-referential, indulgent, overly judgmental, and often hysterical.

Somehow that book "went missing"... We have to write that book ourselves.The reality is that most of us lived our first decades feeling welcome only when certain conditions applied: we felt safe and embraced only when the parental units were getting along, when we were on our best behavior, doing well in school, not causing problems, and had as few needs as possible. If you needed more from them, best of luck.

[...]They liked to think their love was unconditional. That's nice. Sadly, though, the child who showed up at the table for meals was not the child the parents had set out to make. They seemed surprised all over again. They'd already forgotten from breakfast.The parental units were simply duplicating what they'd learned when they were small. That's the system.It wasn't that you got the occasional feeling that you were an alien or a chore to them. You just knew that attention had to be paid constantly to their moods, their mental health levels, their rising irritation, and the volume of beer consumed. Yes, there were many happy memories marbled in, too, of picnics, pets, beaches. But I will remind you now that inconsistency is how experimenters regularly drive lab rats over the edge.A few women in the community reached out to me. They recognized me as a frightened lush. I told them about my most vile behavior, and they said, "Me too!" I told them about my crimes against the innocent, especially me. They said, "Ditto. Yay. Welcome." I couldn't seem to get them to reject me. It was a nightmare and then my salvation.

Trappings and charm wear off... Let people see you. They see your upper arms are beautiful, soft and clean and warm, and then they will see this about their own, some of the time. It’s called having friends, choosing each other, getting found, being fished out of the rubble. It blows you away, how this wonderful event ever happened – me in your life, you in mine.

The two nonnegotiable rules are that you must not wear patchouli oil – we’ll still love you, but we won’t want to sit with you – and that the only excuse for bringing your cell phone to the dinner table is if you’re eagerly waiting to hear that they’ve procured an organ for your impending transplant.

The welcome book would have taught us that power and signs of status can't save us, that welcome – both offering and receiving – is our source of safety. Various chapters and verses of this book would remind us that we are wanted and even occasionally delighted in, despite the unfortunate truth that we are greedy-grabby, self-referential, indulgent, overly judgmental, and often hysterical.

The welcome book would have taught us that power and signs of status can't save us, that welcome – both offering and receiving – is our source of safety. Various chapters and verses of this book would remind us that we are wanted and even occasionally delighted in, despite the unfortunate truth that we are greedy-grabby, self-referential, indulgent, overly judgmental, and often hysterical.