Twenty-seven European countries are marking the European Day of Jewish Culture on Sunday — an initiative aimed at opening the doors of Jewish communities, heritage sites and culture to the non-Jewish world, as well as deepening Jews' own knowledge of their history in Europe.

One of the most enthusiastic participants is Italy, where some 70 towns and cities are holding festivals, exhibits and concerts linked to Jewish traditions.

Outside of Israel, Italy is believed to have the oldest continuing Jewish presence of any country – more than 2,000 years — with catacombs and a synagogue from ancient Rome, as well as synagogues from the Middle Ages, to the Baroque period and the 20th century.

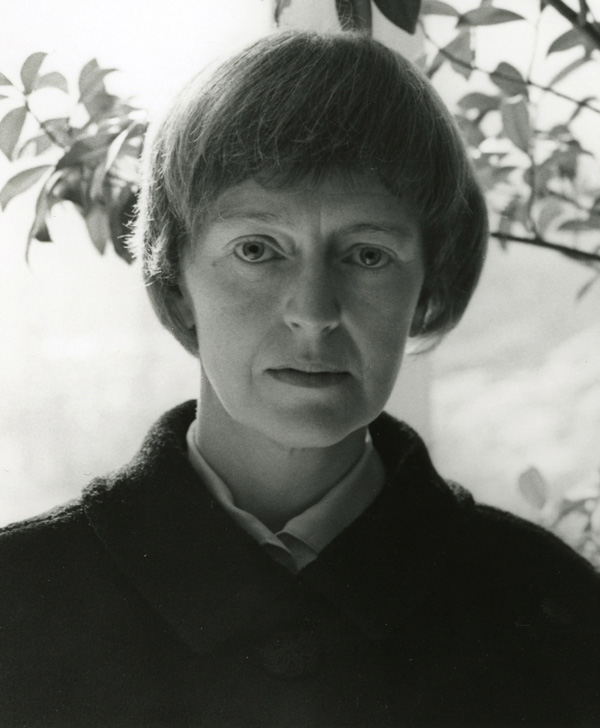

One of the most unique sites is a medieval town in Tuscany — Pitigliano, also known as Little Jerusalem.

Times Of Tolerance, Times Of Persecution

Pitigliano soars majestically over vineyards and olive groves. Its centuries-old multi-storied buildings seem carved out of a massive volcanic tufa rock first settled by the Etruscans.

In the 16th century, while Venice, Rome and Florence were locking Jews up in ghettos, the Orsinis, enlightened rulers of the independent state of Pitigliano, welcomed Jewish traders and craftsmen to boost the local economy.

Sylvia Poggioli/NPR

"They gave them chances to work and open a bank and trading especially in textiles", says tourist guide Paola Blanchi, "and therefore starts this double presence, Jews and Christians all together in a small state".

But Blanchi says that state of civility ended when Pitigliano came under the rule of the Medicis of Florence, who were allied with the Papal State in persecuting Jews.

"[Jews] had to leave their own private property and go and live inside the Jewish quarter, so their trade was no longer so free as it was earlier," he says. And "they had to carry a sign, a yellow sign or tunic."

Pittgliano's best-known delicacy is a stick of pastry filed with honey and walnuts. It's called sfratto — Italian for eviction, recalling the sticks used by Medici officers to knock on Jewish doors and order Jews from their homes and into the ghetto.

A century after the Medicis arrived, Pitigliano again came under enlightened rule. The Grand Duchy of Tuscany granted Jews freedom to live and work where they pleased. At their peak, Jews made up a quarter of Pitigliano's population and enjoyed what came to be known as their golden period.

But by 1938, when the Fascist regime imposed anti-Semitic laws, only 70 Jews were left in Pitigliano.

Today, they're down to four or five.

But every year, tens of thousands of visitors — Jewish and non-Jewish — descend steep stone stairs to visit the Little Jerusalem Association.

Walking Through History And Heritage

The cultural organization comprises the restored synagogue, dating from 1598, and the ritual bath, slaughterhouse and bakery — all three carved out from the tufa rock centuries ago.

In her book Classic Cuisine of the Italian Jews, Edda Servi Machlin recalls her childhood in the 1930s, when the communal oven was in operation only for the week before Passover.

She describes the dangerous but exciting descent down slippery stone steps to a vault-like room that bustled with activity:

"All the Jews of the village would gather, a few families at a time, and prepare their own matzot and all varieties of cookies, sweets and cakes used during the eight days of Passover celebration. Mountains of eggshells would pile up in a few seconds, as everyone went to work with precision and dexterity ... For a few days a procession of enormous wicker baskets full of these goodies would make its way from the cave to the various Jewish residences, leaving a delicious fragrance hovering over the narrow streets — a spectacle that always drew mobs of Christian children to the gateway of the ghetto,"

Judith Elkin, from Poughkeepsie, N.Y., came to visit Pitigliano trying to fill a gap in her knowledge about her Jewish heritage — what came between the stories of the Torah and the time her grandparents emigrated to the U.S. from Europe.

"Out in the diaspora, how did they keep going?" she asks. "I think that is what brings me here. I feel attached — how did they keep going here?"

But most visitors to Pitigliano are not Jewish, like Claudia Malgara, from Milan. Her visit is motivated more by curiosity. "We do not know really the Jewish culture, so it is interesting," she says. "And the memory come back to the people that lived here and now are they dead."

Remembering Jewish Life — Not Just Jewish Deaths

Ruth Ellen Gruber, who writes frequently about Jewish cultural and heritage issues in Europe, says that everything most Italian non-Jews know about Jews is linked to World War II: "You talk about the Holocaust, you talk about death," she says.

Gruber says that Pitigliano is the perfect illustration of the aim of the European day of Jewish Culture — to celebrate Jewish life instead.

Also, she says, it's meant "to promote the idea that Jewish culture is part of European culture, it's not something that is something else. Jews have lived in Europe for centuries, in Italy for millennia — and what developed here is part of the Italian reality, just as the Jewish culture in other parts of Europe is part of European culture."

The day of Jewish Culture has been attracting growing numbers of visitors throughout Europe – last year, 1,000 different events drew close to 100,000 visitors across the continent. And organizers see the annual event as a crucial response to the current surge in anti-Semitism in many parts of Europe.

Comments:

For my part in the 2014

For my part in the 2014

Lovers seek for privacy. Friends find this solitude about them, this barrier between them and the herd, whether they want it or not.

Lovers seek for privacy. Friends find this solitude about them, this barrier between them and the herd, whether they want it or not.