![]()

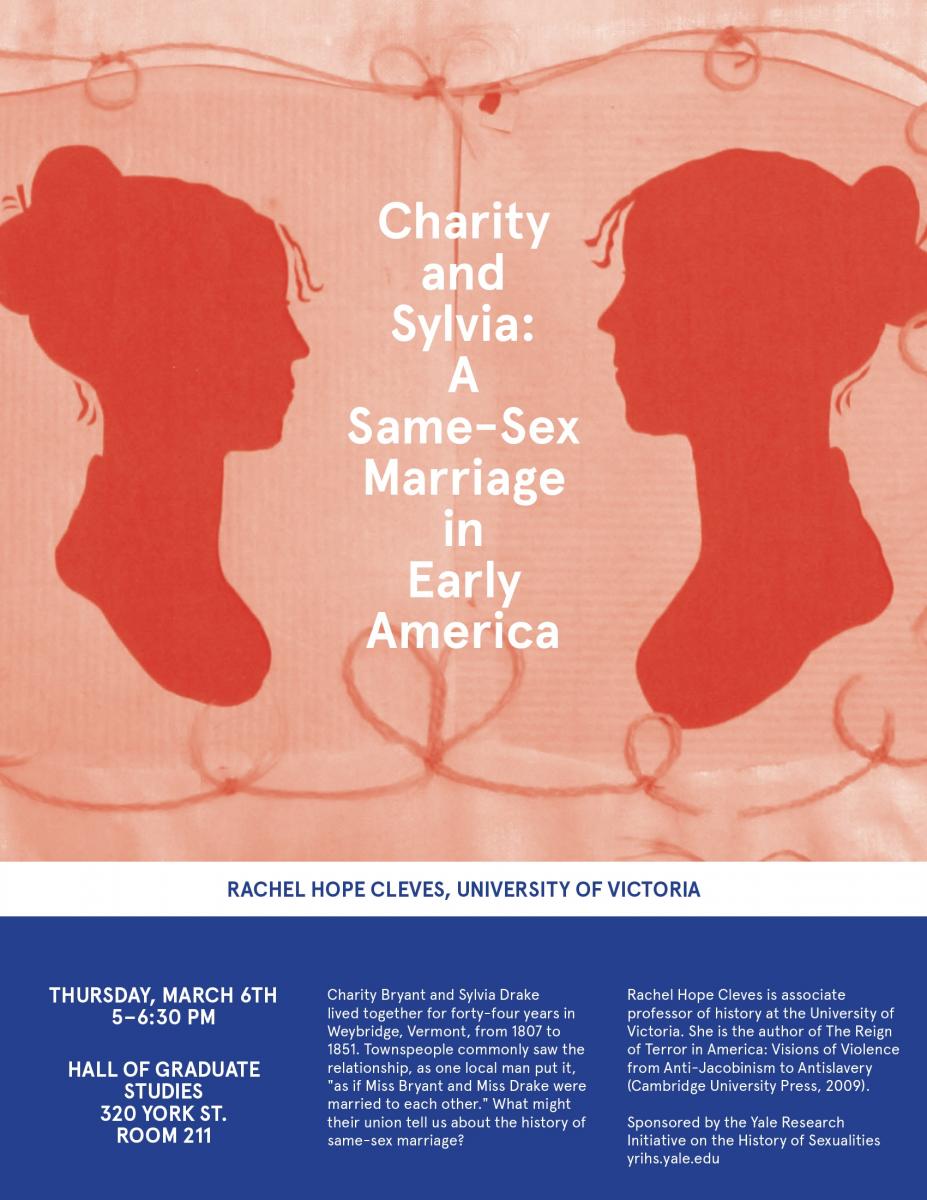

by Maria Popova“For 40 years… they have shared each other’s occupations and pleasures and works of charity while in health, and watched over each other tenderly in sickness.”

In 1897, a man by the name of Hiram Harvey Hurlburt recorded in his diary:

“Miss Bryant and Miss Drake were married to each other.”Nine decades earlier in a neighboring village, more than two centuries before

Edie and Theaclaimed equal dignity for all love in the eyes of the law, 30-year-old Charity Bryant and 22-year-old Sylvia Drake had entered into a lifelong union and promised eternal love to one another, immortalizing their vows in a traditional silhouette portrait. With level eyes and uplifted chins, two elegant black outlines gaze at each other across a thick cream-colored mat, framed by delicate paper with pinkened edges and encircled by a thin braid of blond hair, which forms a heart between their mirrored bosoms.

Reflecting on the symbolism of the silhouette portrait, Cleves writes:

Their sameness is misleading, a misapprehension that obscures their differences from each other, and their difference as a pair from others at the time…

Charity opened the door to a different life. She struck an astonishing contrast to the women in Sylvia’s family, who were all mothers to large and growing families. Sylvia ultimately had sixty-four nieces and nephews; one sister-in-law gave birth to eighteen children, ten by the time Sylvia and Charity met…

[Charity] had pledged at age twenty-three to never get married. Instead [she] poured her creative energies into writing verses, not birthing children. Charity’s singularity and singlehood were intoxicating to Sylvia, who had very little interest in marriage herself. Sylvia dismissed the men who courted her without consideration. The Drakes could not make sense of Sylvia’s aversion. But in Charity, Sylvia finally found a kindred soul.

What an irony that these two marriage-averse women ended up forming such a remarkable union… Once Sylvia and Charity found each other, they were never willing to be parted. Charity described their encounter as “providence.”

Mere months after that fateful first meeting — one imagines something akin to

how Alice B. Toklas met Gertrude Stein — Charity rented a room at Weybridge and on July 3, 1807, Sylvia moved in. Cleves writes:

For the rest of their lives, the two women would celebrate this date as the beginning of their union. Over the next forty-four years they remained mutually devoted to each other through the tribulations of ill health, overwork, and spiritual doubt.

They finally parted when Charity died in 1851. Seventeen lonely years later, Sylvia was buried next to her in the graveyard on Weybridge Hill, under a shared headstone, like any married couple.

![]()

Charity and Sylvia's headstone at Weybridge Hill cemetery

But even though such same-sex unions were not entirely uncommon, what made that between Charity and Sylvia so singular was that it was an open secret — if there was any closet at all, it was wholly transparent, with the entire village looking in:

Although Sylvia and Charity lived a quiet life, far from the bustle and commotion of the nineteenth century’s growing cities, they did not live in secret. Everyone who knew them understood that they were a couple and viewed their relationship as a marriage or something like it… Charity’s nephew, the poet William Cullen Bryant, came close when he described the relationship as “no less sacred to them than the tie of marriage.”

And yet even boldness is beholden to the cultural context of its time — though their marriage was in many ways revolutionary, it simply reappropriated

domestic gender expectations rather than creating new ones altogether:

One reason people viewed Charity and Sylvia’s relationship as marital was that the women divided their domestic and public roles according to the familiar pattern of husband and wife. Throughout their lives together Charity always served as head of the household. Her name came first in public documents, such as tax records and census records. She handled the money and took the leading role in all of their business. Sylvia performed the wifely work of cooking and keeping house. In some ways, she did not live all that differently from her sisters after all.

Hiram Hurlburt explained in his memoir, “Miss Bryant was the man” in the marriage. And Sylvia, according to William Cullen Bryant, was a “fond wife” to her “husband.”

Charity and Sylvia also seem to have viewed their relationship in these terms. Charity portrayed herself as a husband when she called Sylvia her “help-meet” — a common early American synonym for wife, adopted from the Bible, Genesis 2:18. Sylvia fantasized about taking Charity’s name for her own. On an archived scrap of paper, in Sylvia’s handwriting, there survives a list of names that looks like practice toward a signature, with big loops on the capitals and flourishes on the final letters. The list begins with the name “Bryant,” followed by “Bryant Charity,” then plunges into the sequence “Bryant Sylvia Bryant Sylvia Bryant Charity Bryant Sylvia.” Excluded from the legal form of marriage, it appears that Sylvia, in a romantic gesture, once inscribed her desire to become a wife in name as well as practice.

According to English common-law tradition, wives assumed their husbands’ names because marriage transformed spouses into a single person. Genesis 2:24 states that “a man shall cleave unto his wife: and they shall be one flesh.” The idea that a husband and wife became one person, in spirit, body, and law, lay at the heart of early American ideas of marriage. The eighteenth-century English jurist William Blackstone described husbands and wives as one person in the law. Charity shared Sylvia’s evident wish for marital oneness. “May we pass our whole life,” Charity serenaded Sylvia in an 1810 poem, “and our minds be united in one.” Her language echoed an early nineteenth-century English treatise, which defined husbands and wives as “united in one body out of two by God.”

But perhaps most interesting of all is the transparency of their marriage. Indeed, that proverbial closet appears less like a closet than like a translucent Japanese parlor screen — as in their wedding portrait, one can see the women’s silhouettes, the outlines of the relationship, and interpret them with one’s chosen degree of realism, fill them in with as much social propriety as one needs to feel proper oneself.

![]()

Photograph from 'The Invisibles,' a compendium of archival images of queer couples celebrating their love. Click image for more.

Cleves considers the question of freely relinquished privacy:

Like queer people in many times and places, Charity and Sylvia preserved their reputations by persuading their community to treat the matter of their sexuality as an open secret. Although it is commonly assumed that the “closet” is an opaque space, meaning that people who are in the closet keep others in total ignorance about their sexuality, often the closet is really an open secret. The ignorance that defines the closet is as likely to be a carefully constructed edifice as it is to be a total absence of knowledge. The closet depends on people strategically choosing to remain ignorant of inconvenient facts…

The open closet is an especially critical strategy in small towns, where every person serves a role, and which would cease to function if all moral transgressors were ostracized. Small communities can maintain the fiction of ignorance in order to preserve social arrangements that work for the general benefit. Queer history has often focused on the modern city as the most potent site of gay liberation, since its anonymity and living arrangements for single people permitted same-sex-desiring men and women to form innovative communities. More recognition needs to be given to the distinctive opportunities that rural towns allowed for the expression of same-sex sexuality.

[...]

Charity and Sylvia gained the toleration of their relatives and community not by hiding away but by being public-minded… They became “Aunt Charity” and “Aunt Sylvia” to the whole community… [Their] relationship, far from hidden, was widely known and respected. In fact, the absence of a man in their household allowed the women’s marriage less privacy than traditional unions received. In a male-dominated world, two women could not claim the same freedom from public interference that a man could for his home.

![]()

Photograph from 'The Invisibles,' a compendium of archival images of queer couples celebrating their love. Click image for more.

The first formal account of the women’s marriage came from Charity’s nephew, Cullen, who wrote about it in the New-York Evening Post in 1843, as Charity and Sylvia were celebrating their fortieth anniversary. Charity supported Cullen’s poetic aspirations from a young age and he went on to become a writer. In 1850, he published a book of letters, in which he wrote a lyrical account of Charity and Sylvia’s life together, inspired by a popular marriage passage in The Book of Common Prayer:

If I were permitted to draw aside the veil of private life, I would briefly give you the singular, and to me most interesting history of two maiden ladies who dwell in this valley. I would tell you how, in their youthful days, they took each other as companions for life, and how this union, no less sacred to them than the tie of marriage, has subsisted, in uninterrupted harmony, for forty years, during which they have shared each other’s occupations and pleasures and works of charity while in health, and watched over each other tenderly in sickness; for sickness has made long and frequent visits to their dwelling. I could tell you how they slept on the same pillow and had a common purse, and adopted each other’s relations, and how one of them, more enterprising and spirited in her temper than the other, might be said to represent the male head of the family, and took upon herself their transactions with the world without, until at length her health failed, and she was tended by her gentle companion, as a fond wife attends her invalid husband. I would tell you of their dwelling, encircled with roses, which now in the days of their broken health, bloom wild without their tendance, and I would speak of the friendly attentions which their neighbors, people of kind hearts and simple manners, seem to take pleasure in bestowing upon them, but I have already said more than I fear they will forgive me for, if this should ever meet their eyes, and I must leave the subject.

But the story, Cleves notes with a charming wink at her profession (“Historians, unlike poets, are not content with evocative imagery. We have a ravenous appetite for the factual.”), so woven as much of such second-hand accounts as it is of first-hand silences — once again, the negative space shapes the silhouette, adding by leaving out:

Not only have few of the women’s letters survived, the documents that do remain are mostly silent on the subject that first sparked my interest and probably the interest of most readers: the women’s sexuality. Some of the strongest evidence for the women’s sexual relationships appears in their religious writings, where they struggled with the burden of secret sins that left both women feeling uncertain about their redemption. Romantic letters and poems hint at more positive aspects of the women’s physical relationship. In both these sources, references to sexuality take the form of allusions, not direct statements. Respectable nineteenth-century women rarely wrote directly about sex of any sort, but this silence is especially characteristic of the history of same-sex intimacy. For many centuries, sex between women or between men was referred to as “the mute sin” or the “crime not fit to be named.”

Even famous lovers like

Oscar Wilde and Alfred “Bosie” Douglas, Cleves points out, called their longtime relationship “the love that dare not speak its name.” What’s singular about the women’s story is that they did speak, if sidewise, to the true nature of their relationship. As such, it reveals just how much more tolerant early America was of same-sex marriage than most people realize. Cleves writes:

Charity’s and Sylvia’s lives tell a more complicated story, revealing the gap that existed between prescription and practice, the rules that govern society and how societies actually operate… More astonishing still, society could also tolerate such sexual possibilities through manufactured ignorance, creating opportunities for same-sex sexuality that should ostensibly have been impossible.

[...]

Same-sex marriage is not as new as Americans on both sides of today’s debate tend to assume; it is neither the radical break with timeless tradition that conservatives fear nor the unprecedented innovation of a singularly tolerant age that liberals praise. It fits within a long history of marriage diversity in North America that included practices such as polygamy, self-divorce, free love, and interracial unions… Through their union, Charity and Sylvia undermined the conventional definitions of womanhood and manhood that ordinary marriages reinforced. They staked out new claims to familial, economic, and spiritual authority that were denied to their conventionally married sisters. It seems reasonable to hope that same-sex marriage has the same potential to reshape acceptable sex roles today.

In that regard, Cleves — who chanced upon Charity and Sylvia’s story by complete accident while browsing a local history museum — reflects on the broader importance of mining history for evidence of social phenomena we mistakenly believe to be unique to our age:

The research process has left me more sure than ever that there are countless pieces remaining to be found, if not from Charity’s and Sylvia’s lives then from the lives of other lovers who lived outside the norms. Their stories have been hard to see because they confound our expectations. We see each story as one of a kind, defying categorization. Taken together they tell a history we are only beginning to know. The most remarkable element of Charity and Sylvia’s life together, in the final assessment, may be how unremarkable it was.

Charity & Sylvia is an absorbing and perspective-shifting read in its entirety, chronicling the lives of these two pioneering women, the multitude of challenges, personal and social, they overcame to be together, and the depth and richness of their lifelong love. Complement it with

the greatest queer love letters of all time, including Virginia Woolf, Oscar Wilde, Margaret Mead, and Edna St. Vincent Millay, then revisit the

passionate correspondence of Vita Sackville-West and Violet Trefusis and these

moving vintage photographs of queer couples celebrating their love in the early twentieth century.

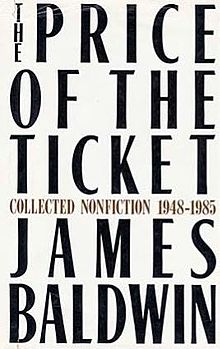

Throughout our nervous history, we have constructed pyramidic towers of evil, ofttimes in the name of good. Our greed, fear and lasciviousness have enabled us to murder our poets, who are ourselves, to castigate our priests, who are ourselves. The lists of our subversions of the good stretch from before recorded history to this moment. We drop our eyes at the mention of the bloody, torturous Inquisition. Our shoulders sag at the thoughts of African slaves lying spoon-fashion in the filthy hatches of slave-ships, and the subsequent auction blocks upon which were built great fortunes in our country. We turn our heads in bitter shame at the remembrance of Dachau and the other gas ovens, where millions of ourselves were murdered by millions of ourselves. As soon as we are reminded of our actions, more often than not we spend incredible energy trying to forget what we've just been reminded of.

Throughout our nervous history, we have constructed pyramidic towers of evil, ofttimes in the name of good. Our greed, fear and lasciviousness have enabled us to murder our poets, who are ourselves, to castigate our priests, who are ourselves. The lists of our subversions of the good stretch from before recorded history to this moment. We drop our eyes at the mention of the bloody, torturous Inquisition. Our shoulders sag at the thoughts of African slaves lying spoon-fashion in the filthy hatches of slave-ships, and the subsequent auction blocks upon which were built great fortunes in our country. We turn our heads in bitter shame at the remembrance of Dachau and the other gas ovens, where millions of ourselves were murdered by millions of ourselves. As soon as we are reminded of our actions, more often than not we spend incredible energy trying to forget what we've just been reminded of.