Clare Carter

"Republican Politicians On Rape"

http://paxonbothhouses.blogspot.com/2014/01/republican-politicians-on.html

http://paxonbothhouses.blogspot.com/2014/01/republican-politicians-on.html

Long before LGBTQ rights were on many countries' radars, South Africa banned discrimination against gay people in 1996 and legalized same-sex marriage in 2005—the fifth country in the world to do so. Yet many gay men and lesbians in this patriarchal society face extreme and sometimes deadly discrimination. In 2008, a South African lesbian soccer player training for the World Cup was raped and murdered in a crime known as “corrective rape.” The term, believed to originate in South Africa due to its prevalence there, refers to when gay men or women are raped to “cure” them of their sexual orientation; the hate crime is almost never reported or prosecuted.

When British photographer Clare Carter heard of these crimes, she was surprised that the gay community would be so violently targeted. “I didn’t understand the contradictions,” Carter said. “I couldn’t understand why people were being assaulted for having loving relationships and why the individual’s right to choose who they love was causing such conflicts.”

After researching the issue, Carter headed to South Africa on one of many trips she took over a two-year period while working in New York assisting photographer Nan Goldin. She decided to work on a project that was comprehensive enough to show the victims of corrective rape and to underscore the problem’s scope of culpability.

Clare Carter

Clare Carter

Clare Carter

She began by connecting with people involved with NGOs in South Africa—some of whom had been victims of corrective rape—who then put her in touch with other victims. The more she visited and gained the trust of people, the more she would be introduced to victims and to people indirectly involved, including priests who believe homosexuality can be changed and police who often did little to protect those who came forward about their attacks. “It was like peeling an onion,” Carter said. “Just layer upon layer, and there was always more to the story. It’s never black and white: cultural, religious, familial—they all have a hand in what’s happening.”

Despite the country’s progressive laws, South African men use corrective rape as a means of asserting their masculinity and frustration with the liberal laws, Carter said. She said many men don’t like or don’t understand why a woman would wear her hair short or wouldn’t wear a dress. “What I was being told about gender and sexuality [by the perpetrators] was: ‘Why are you stealing our girlfriends? We’re going to rape you and show you what it is like to be a woman,’ ” Carter said. “They don’t understand the relationship between being a woman and feeling attractive to other women.”

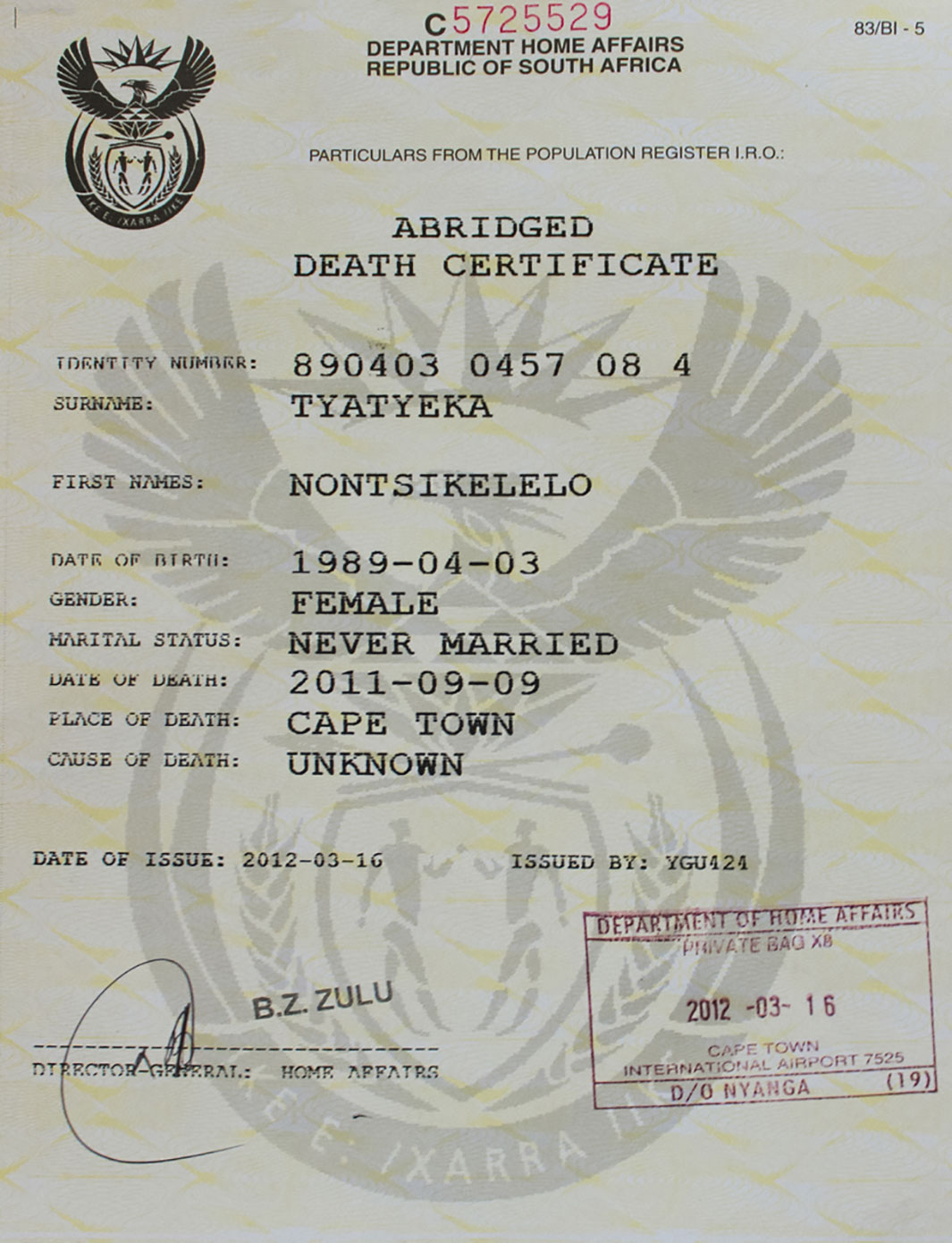

To create a visual storyboard of what she discovered, Carter included death certificates, scenes of the crimes, and other shots of evidence. Carter also decided to photograph the women with a classic sense of portraiture, something she said is common in her other work, to capture the women’s bravery. “One might expect survivors to become more insular and protective about who they are after a corrective rape, but most are not—that’s what was so empowering to me,” she said. “Most don’t change the way they dress or act or wear their hair. They are showing that the men who are perpetrating these homophobic attacks aren’t winning, and they are staying true to who they are.”

Carter is currently working on a book about the project. Although she feels the project’s photography is finished, she says her work as an activist and supporter of the NGOs she worked with will continue.

Clare Carter

Clare Carter

Clare Carter

Clare Carter

Clare Carter