How Should We Live: History’s Forgotten Wisdom on Love, Time, Family, Empathy, and Other Aspects of the Art of Living

by Maria Popova“How to pursue the art of living has become the great quandary of our age… The future of the art of living can be found by gazing into the past.”

“He who cannot draw on three thousand years is living from hand to mouth,” Goethe famously proclaimed. Thomas Hobbes extolled “the principal and proper work of history being to instruct, and enable men by the knowledge of actions past to bear themselves prudently in the present and providently in the future.” It is this notion of “applied history” that cultural historian and philosopher Roman Krznaric — who gave us How to Find Fulfilling Work, one of the best psychology and philosophy books of 2013 — places at the center of How Should We Live?: Great Ideas from the Past for Everyday Life (public library). Part psychological manual, part cultural manifesto, part philosophical memoir of our civilization’s collective conscience, the book explores yesteryear’s great works of philosophy, social science, economics, anthropology, and cultural mythology. Krznaric trawls the timeless to surface the timely and excavate practical ideas about the art of living, about how we, today, can live better, richer, more fulfilling lives — ideas across love, work, family, time, money, death, creativity, and more.

“He who cannot draw on three thousand years is living from hand to mouth,” Goethe famously proclaimed. Thomas Hobbes extolled “the principal and proper work of history being to instruct, and enable men by the knowledge of actions past to bear themselves prudently in the present and providently in the future.” It is this notion of “applied history” that cultural historian and philosopher Roman Krznaric — who gave us How to Find Fulfilling Work, one of the best psychology and philosophy books of 2013 — places at the center of How Should We Live?: Great Ideas from the Past for Everyday Life (public library). Part psychological manual, part cultural manifesto, part philosophical memoir of our civilization’s collective conscience, the book explores yesteryear’s great works of philosophy, social science, economics, anthropology, and cultural mythology. Krznaric trawls the timeless to surface the timely and excavate practical ideas about the art of living, about how we, today, can live better, richer, more fulfilling lives — ideas across love, work, family, time, money, death, creativity, and more.He writes in the introduction:

How to pursue the art of living has become the great quandary of our age.[…]I believe that the future of the art of living can be found by gazing into the past. If we explore how people have lived in other epochs and cultures, we can draw out lessons for the challenges and opportunities of everyday life. What secrets for living with passion lie in medieval attitudes towards death, or in the pin factories of the Industrial Revolution? How might an encounter with Ming-dynasty China, or Central African indigenous culture, change our views about bringing up our kids and caring for our parents? It is astonishing that, until now, we have made so little effort to unveil this wisdom from the past, which is based on how people have actually lived rather than utopian dreamings of what might be possible.I think of history as a wonderbox, similar to the curiosity cabinets of the Renaissance — what the Germans called a Wunderkammer. Collectors used these cabinets to display an array of fascinating and unusual objects, each with a story to tell, such as a miniature Turkish abacus or a Japanese ivory carving. Passed down from one generation to another, they were repositories of family lore and learning, tastes and travels, a treasured inheritance. History, too, hands down to us intriguing stories and ideas from a cornucopia of cultures. It is our shared inheritance of curious, often fragmented artefacts that we can pick up at will and contemplate in wonder. There is much to learn about life by opening the wonderbox of history.

Rather than approaching that wonderbox as an instructional manual, however, Krznaric looks at history as a choose-your-own-adventure compendium of do’s as well as don’ts. In addition to shining light on yesteryear’s forgotten wisdom on living, he also seeks to highlight the habitual attitudes we’ve unwittingly inherited from the past and to bring mindfulness to the bad and the harmful as well, so we can begin to decondition them — those toxic belief systems that sell us impossible romantic ideals, strain our relationship with time, force us into work that falsely prizes narrow specialization over wide intellectual expansion, measure our success in material terms, and otherwise warp the meaning of life:

We need to trace the historical origins of these legacies which have quietly crept into our lives and surreptitiously shaped our worldviews. We may choose to accept them, understanding ourselves all the better for it, or we may reject them and cut ourselves free from an unwanted inheritance, ready to invent anew. That is the sublime power we wield when we have history in our hand.

In a chapter on love, Krznaric contends that our modern definition of love is too narrow, which both deprives us of the breadth of this grand human capacity and sets us up for disappointment:

We can navigate these difficulties of love — and enhance its joys — by grasping the significance of two great tragedies in the history of the emotions. The first is that we have lost knowledge of the different varieties of love that existed in the past, especially those familiar to the ancient Greeks, who knew love could be discovered not just with a sexual partner, but also in friendships, amongst strangers, and with themselves. The second tragedy is that over the last thousand years, these varieties have been incorporated into a mythical notion of romantic love, which compels us to believe that they can all be found in one person, a unique soulmate. We can escape the confines of this inheritance by looking for love outside the realm of romantic attachments, and cultivating its many forms.

To lift our culturally conditioned blinders, he turns to the six varieties of love found in ancient Greek philosophy: eros, or sexual passion; phila, a more virtuous love often translated as “friendship”; ludus, the playful affection between children or casual lovers; pragma, the mature love and deep understanding that develop in lasting relationships; agape, the selfless love extended to all human beings, offered unconditionally and with no expectation of reciprocity; and philautia, or self-love, which can be both negative, manifested as greed and narcissism (after the myth of Narcissus), and positive, as a nourishing broadening of our capacity for all love, starting from within.

Vintage illustration for Homer's 'The Iliad and the Odyssey' by Alice and Martin Provensen. Click image for details.

Observing history’s long quest to define love, Krznaric finds in the ancient Greek model solace for our modern hearts:

One of the universal questions of emotional life has always been, “What is love?” I believe that this is a misleading question, and one which has caught us in futile knots of confusion in an attempt to identify some definitive essence of “true love.” The lesson from ancient Greece is that we must instead ask ourselves, “How can I cultivate the different varieties of love in my life?” That is the ultimate question of love that we face today. But if we wish to nurture these varieties, we must first dispel the potent myth of romantic love which stands in the way.

Krznaric argues that the myth of romantic love, whose origin he traces across three stages over the course of civilization — the poetry and music of medieval Persia in the first millennium, the courtly love ideal of Europe in the Middle Ages, and the utilitarian union of passion and companionship of the Dutch Golden Age in the seventeenth century — is a toxic myth that only robs us of love’s dimension and leads us to believe all forms of love should be found in a single person. Instead, he suggests that returning to the ancient Greek taxonomy would enrich our lives and give greater freedom in cultivating our capacity for love:

The varieties of love invented by the ancient Greeks … are what we should be striving to cultivate, and with a range of people rather than just one person. I am not saying that you should get your pragma from a steady marriage but then satisfy your eros in a series of lustful affairs. That is bound to be a destructive strategy, for sexual jealousy is part of our natures and few people can tolerate open relationships. What I mean is that we ought to acknowledge that we may only be fulfilled in love if we can nurture it in a multitude of ways and tap into its many sources. So we should foster our philiathrough having profound friendships outside our main relationship, and make space for our lover to do the same without resenting the time they spend apart from us. We can seek the joys of ludus not just in sex but in other forms of play, from tango dancing and performing in amateur theatre to laughing with children around the family dining table. And we must recognize that being drawn too far into self-love, or limiting our love to only a small circle of people, will not be enough to meet our inner need to feel part of a larger whole. So we should all make a place for agape in our lives, and transform love into a gift for strangers. That is how we can reach a point where our lives feel abundant with love.

In a chapter on family, Krznaric explores the lost history of the househusband — presently an exotic species statistically outnumbered by housewives by a ratio of forty to one, and yet a species that used to be far more common in pre-industrial society. In a chapter on empathy, he invokes the famous anecdote of St. Francis swapping his clothes with a beggar in order know what it was like to be a pauper, then writes:

Empathy matters not just because it makes you good, but because it is good for you. It has the power to heal broken relationships, erode our prejudices, expand our curiosity about strangers and make us rethink our ambitions. Ultimately empathy creates the human bonds that make life worth living.

He once again offers an important caveat to our current cultural understanding — or misunderstanding — of empathy:

It is important when thinking about empathy to distinguish it from the so-called Golden Rule: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” Although a worthy notion, it is not empathy, since it involves considering how you — with your own views — would wish to be treated. Empathy is harder: it requires imagining others’ views and then acting accordingly. George Bernard Shaw understood the difference when he remarked, “Do not do unto others as you would have them do unto you — they may have different tastes.”

But it is another legendary writer to whom Krznaric points as the “one person who did more than most others to transform this experiential form of empathy into an extreme sport” — George Orwell. Raised in a privileged upper-middle-class British family, with the benefit of an elite education, Orwell found himself suddenly disillusioned with imperialism when he spent five years as a colonial officer in Burma in his early twenties. More than that, he couldn’t live with his own contribution to the system he came to so vehemently disdain — he wrote that the job made him “see the dirty work of Empire at close quarters” and left him oppressed “with an intolerable sense of guilt.” Those five years were Orwell’s training ground for empathy. Krznaric traces how the beloved writer put his own twist on the St. Francis approach:

If Burma was his apprenticeship as an empathist, Orwell’s formative training took place in London in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Determined to be a writer, he came up with a plan that would give him both a literary and a moral education: to conduct a radical experiment in experiencing poverty. He wanted to know what it was really like to be downtrodden, to exist on the margins of society, to be short of food, money and hope. Reading about it was not enough — his aim was to live it.[…]So, for several years, Orwell regularly dressed as a tramp in shabby clothes and shoes, and ventured out virtually penniless to frequent the “spikes” — hostels for the homeless — and doss-houses of the East End of London, wandering the streets with beggars and other destitutes. He would stay for anything from a few days to several weeks. At all times he did so without concessions or compromise, without carrying spare money for an emergency or wearing extra layers of clothes against the winter cold.[…]Orwell’s empathy grew out of an attempt to liberate himself from his elite background and the imperialism of which he had been a foot soldier. But he also wanted to touch injustice with his own hands rather than be just another clever intellectual who pitied the poor from a comfortable distance. And in this he undoubtedly succeeded.He also succeeded in showing how empathy was about far more than ethics. His tramping excursions certainly challenged his prejudices and shifted his moral values, but they also gained him new friendships, nurtured his curiosity, expanded his ability to talk to people from different social backgrounds and provided him with a rich seam of literary materials which would last him for years. For a young man who had once worn a top hat at Eton,his experiments in living down and out were an intense, exhilarating and often challenging lesson in life itself, catapulting him out of the narrowness of his privileged past. Trying to survive on the streets of East London was the greatest travel experience he would ever have.

Though Krznaric notes that few of us can go to the extremes Orwell did in our pursuit of embodied empathy, he draws from the writer’s experience a seemingly simple yet, when applied, profound everyday aspiration:

The idea of empathy has distinct moral overtones and is often associated with “being good.” But experiential empathy should really be regarded as an unusual and stimulating form of travel. George Orwell would tell us to forget spending our next vacation at an exotic resort or visiting standard tourist sites. It is far more interesting to expand our minds by taking journeys into other people’s lives — and allowing them to see ours. Rather than asking ourselves, “Where can I go next?,” the question on our lips should be, “Whose shoes can I stand in next?”

But my favorite is a chapter in which Krznaric considers our strange relationship with time — that peculiar dimension of life that we’ve attempted to measure and make palpable since the dawn of, well, time. Given how profoundly metaphors shape our thoughts and emotions, Krznaric makes an especially pause-giving point in exploring how our flawed metaphors for time — much like our flawed metaphors for memory — deform our experience of it:

Our concept of time is similarly structured by metaphors, and we need to become aware of the subtle ways they work on our minds. One of the most prevalent metaphors already mentioned, which emerged during the Industrial Revolution, is of time as a commodity: spending time, buying time, wasting time, saving time, “time is money,” “living on borrowed time.” Another dating from the same period is time as a possession: “my time is my own,” “give me a moment of your time.” These two metaphors, in tandem, constitute the psycholinguistic roots of our problems with time. If our time is like private property, it becomes possible not only for it to be freely granted to others, but possibly owned by them or appropriated at an unfair price against our wishes.

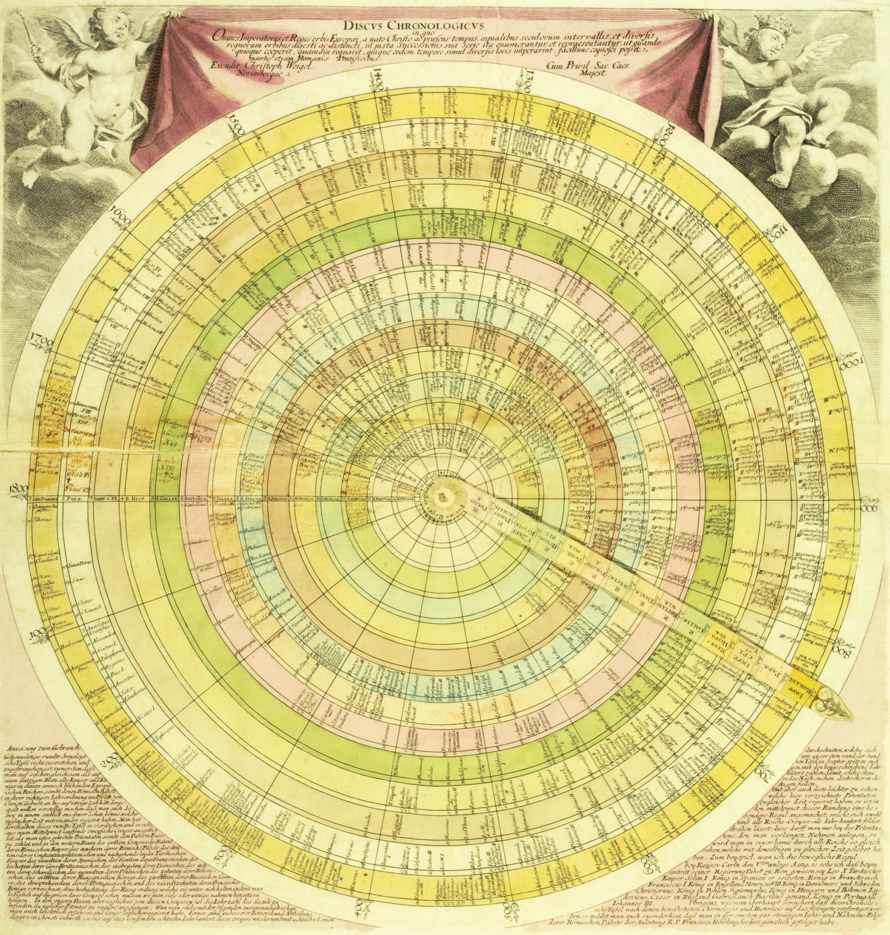

Discus chronologicus by German engraver Christoph Weigel, a timekeeping chart circa 1720s. Click image for details.

I’ve always been extremely wary of the notion of “work-life balance,” which pits work as something undesirable that takes away from the desirable parts of life and must thus be balanced against those, kept to a reasonable level, quarantined. This dichotomy leaves no room for the kind of purposeful workthat is life. Curiously, the very concept of “work-life balance” tends to use time as the currency by which balance is measured, so I find Krznaric’s admonition against conceiving of time as a commodity especially resonant when it comes to how we think about work and play:

One manifestation of the “time as a commodity and possession” metaphor is when we talk about taking “time off” from work. This expression is essentially saying that we have given our employer ownership of our time. . . . Each year the firm will give us back a little of our time, usually no more than a few weeks. This vacation period is usually referred to as “time off”; it is their gift to us, a temporary pause in the regular pattern, in which being at work is, by implication, “time on.”

Instead, he proposes we think of leisure as our “time on,” which would imbue our non-work time with value and awaken from the cultural trance that consistently blinds us to how much more precious presence is than productivity.

Krznaric traces the history of time as a commodity to the dawn of the Protestant ethic, which equates productivity and efficiency with virtue. Coupled with that is the cultural legacy of our fear of boredom, beneath which Krznaric finds a deeper anxiety:

On some level we fear boredom. A deeper explanation is that we are afraid that an extended pause would give us the time to realize that our lives are not as meaningful and fulfilled as we would like them to be. The time for contemplation has become an object of fear, a demon.

He argues that we can begin to undo this baleful legacy by borrowing the mindset of Gustave Flaubert, who famously observed that “anything becomes interesting if you look at it long enough.” Krznaric even proposes a somewhat radical pragmatic intervention: a “chronological diet” that banishes timekeeping devices from your wrist, your smartphone display, and your walls — a tactic, however disorienting at first, that promises to make you “less likely to interrupt a conversation or a thought with a glance at your watch which sends you scuttling off to the next task.”

How Should We Live?: Great Ideas from the Past for Everyday Life, an illuminating and awakening read in its entirety, goes on to explore how Michelangelo deformed how we think about creativity and precipitated the dangerous myth of the sole genius, why money is not enough, what the Toltec and Aztec civilizations teach us about our understanding of mortality, and much more. Complement it with George Myerson’s exploration of what history teaches us about attaining everyday happiness.