November 27, 1965: A Rare Recording of Stanley Kubrick’s Most Revealing Interview

by Maria Popova“People react primarily to direct experience and not to abstractions; it is very rare to find anyone who can become emotionally involved with an abstraction.”

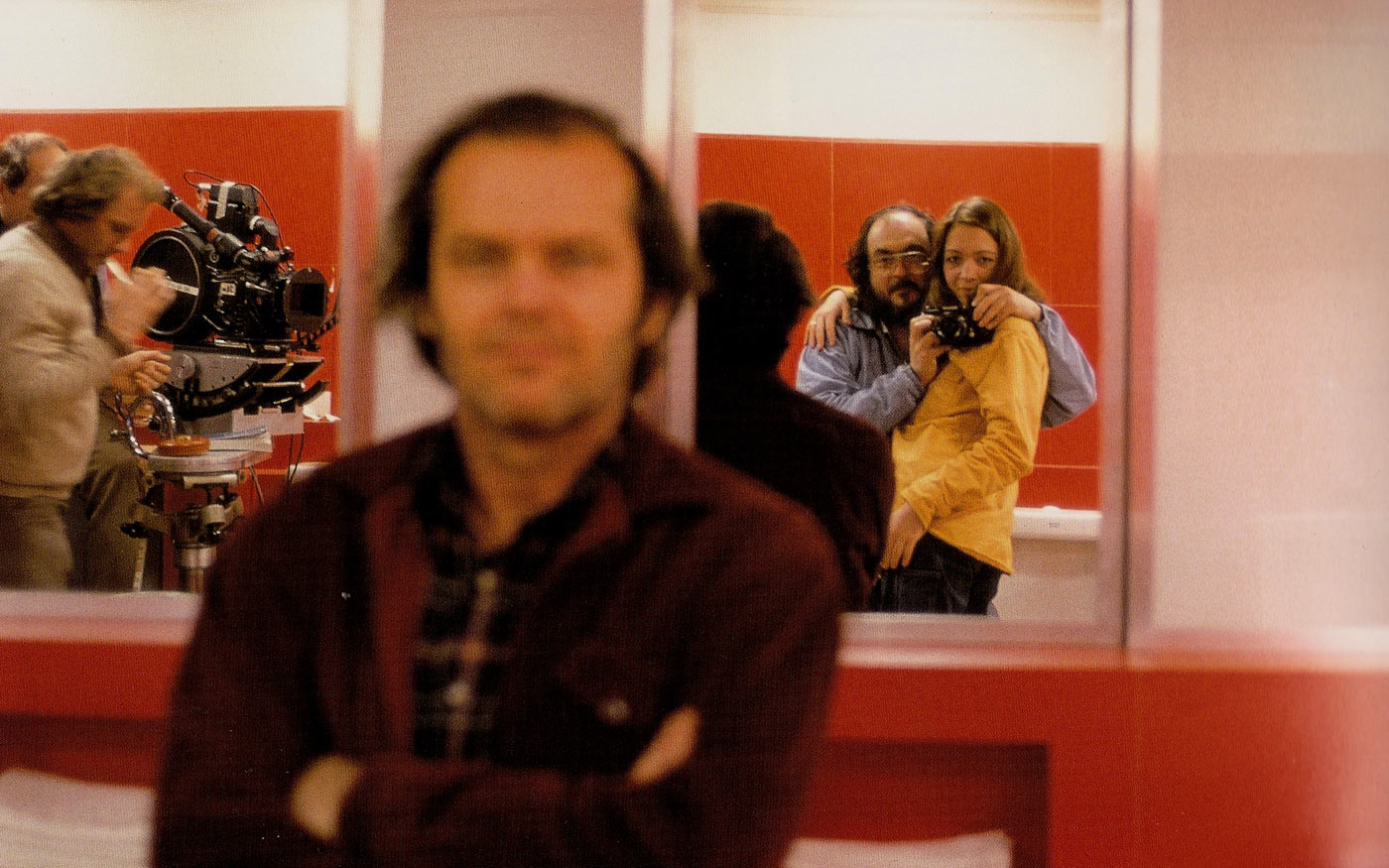

In the spring of 1965, the physicist and prolific author Jeremy Bernstein wrote a short piece for The New Yorker’s “Talk of the Town” about of 37-year-old director Stanley Kubrick, who was accelerating towards the zenith of his cultural acclaim after releasing Lolita and Dr. Strangelove and was about to release his greatest film, his cult collaboration with Arthur C. Clarke, 2001: A Space Odyssey. The piece garnered enough interest that Bernstein was assigned to write a feature-length profile of Kubrick — something the reclusive director wouldn’t have ordinarily agreed to, had it not been for one peculiar passion he shared with Bernstein: the love of chess. So Bernstein traveled to Oxford, where 2001 was being shot, and spent ample time with Kubrick, sneaking in chess matches during production breaks. And even though he never beat Kubrick, he accomplished an even greater feat: He got the young director, notoriously averse to long interviews, to engage in a 76-minute conversation, recorded on tape. This rare audio, recorded on November 27, 1965, is arguably Kubrick’s most extensive and revealing interview about his early career, discussing such wide-ranging subjects as how he learned that problem-solving is the key to creative success, why he got bad grades in high school, the promise and perils of nuclear power, the allure of space exploration, and what it was like to work with Clarke and Nabokov.

In the spring of 1965, the physicist and prolific author Jeremy Bernstein wrote a short piece for The New Yorker’s “Talk of the Town” about of 37-year-old director Stanley Kubrick, who was accelerating towards the zenith of his cultural acclaim after releasing Lolita and Dr. Strangelove and was about to release his greatest film, his cult collaboration with Arthur C. Clarke, 2001: A Space Odyssey. The piece garnered enough interest that Bernstein was assigned to write a feature-length profile of Kubrick — something the reclusive director wouldn’t have ordinarily agreed to, had it not been for one peculiar passion he shared with Bernstein: the love of chess. So Bernstein traveled to Oxford, where 2001 was being shot, and spent ample time with Kubrick, sneaking in chess matches during production breaks. And even though he never beat Kubrick, he accomplished an even greater feat: He got the young director, notoriously averse to long interviews, to engage in a 76-minute conversation, recorded on tape. This rare audio, recorded on November 27, 1965, is arguably Kubrick’s most extensive and revealing interview about his early career, discussing such wide-ranging subjects as how he learned that problem-solving is the key to creative success, why he got bad grades in high school, the promise and perils of nuclear power, the allure of space exploration, and what it was like to work with Clarke and Nabokov.The profile, fittingly titled “How About a Little Game?,” was published nearly a year later, in the November 12, 1966 issue of The New Yorker, and was eventually included in Stanley Kubrick: Interviews (public library) — the same excellent collection that gave us Kubrick’s Playboy interview on mortality, the fear of flying, and the meaning of life. One of the most interesting — and prescient — subjects discussed in both the New Yorker article and the audio interview are Kubrick’s conflicted views on nuclear power and the atomic bomb. Bernstein writes:

It was the building of the Berlin Wall that shaped Kubrick’s interest in nuclear power and nuclear strategy, and he began to read everything he could get hold of about the bomb. Eventually, he had decided that he had about covered the spectrum, and wasn’t learning anything new. “When you start reading the analyses of nuclear strategy, they seem so thoughtful that you’re lulled into a temporary sense of reassurance,” Kubrick explained. “But as you go deeper into it, and become more involved, you begin to realize that every one of these lines of thought leads to a paradox.” It is this constant element of paradox in all the nuclear strategies and in the conventional attitudes toward them that Kubrick transformed into the principal theme of Dr. Strangelove.

Kubrick goes on to argue that nuclear energy and the atomic bomb have been reduced to an abstraction, one “represented by a few newsreel shots of mushroom clouds,” which hinders people’s ability to actually engage with the reality of the issue. He tells Bernstein:

People react primarily to direct experience and not to abstractions; it is very rare to find anyone who can become emotionally involved with an abstraction. The longer the bomb is around without anything happening, the better the job that people do in psychologically denying its existence. It has become as abstract as the fact that we are all going to die someday, which we usually do an excellent job of denying. For this reason, most people have very little interest in nuclear war. It has become even less interesting as a problem than, say, city government, and the longer a nuclear event is postponed, the greater becomes the illusion that we are constantly building up security, like interest at the bank. As time goes on, the danger increases, I believe, because the thing becomes more and more remote in people’s minds. No one can predict the panic that suddenly arises when all the lights go out — that indefinable something that can make a leader abandon his carefully laid plans. A lot of effort has gone into trying to imagine possible nuclear accidents and to protect against them. But whether the human imagination is really capable of encompassing all the subtle permutations and psychological variants of these possibilities, I doubt. The nuclear strategists who make up all those war scenarios are never as inventive as reality, and political and military leaders are never as sophisticated as they think they are.

And yet, despite this glib view of our capacity for transcending the limitations of our own minds, Kubrick did have beautiful faith in the human spirit, as his timeless words bespeak: “However vast the darkness, we must supply our own light.”

![]()

'