1. Jack Kerouac

The gentleman we can blame for hipsters and a prolific collection of beautiful, anti-establishment prose was a Catholic. He was no angel, and certainly not a practicing Catholic (he stopped attending Mass at 14), but it has been rightly pointed out that Jack Kerouac never left his Catholicism. The beat revolution — which later seemed to think Kerouac was advocating moral relativism and playing crap music in coffee houses (which led to the hippies, who led to the hipsters) — largely misunderstood Kerouac’s writing and philosophy, which was informed by a rich, pre-Vatican II Catholicism. From a biography by Dennis McNally, Desolate Angel:

“He was obsessed, enraged, with a sense of America being debauched by the clanking, alienating horror called the new industrial state. Secondly, his rage was cut with a sense of Dostoyevskian suffering and guilt, for he felt that the American citizen’s complicity in the exploiting modern state went far too deep to be ‘solved’. Racism and violence were not issues — “Issues” he’d say with a curling sneer, ”F*ck issues” – but sins, and for that only penance was possible.”

His coining of the term “the beat generation” comes from “the beatific generation”, for — despite all the sin, desperation, existential displacement, and drug abuse — Kerouac believed that his generation would see God. “Beatific generation” was inspired by a vision Kerouac had of a statue of the Virgin Mary turning her head toward him. He said:

“It is because I am Beat, that is, I believe in beatitude and that God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten son to it… Who knows, but that the universe is not one vast sea of compassion actually, the veritable holy honey, beneath all this show of personality and cruelty?”

I found an excellent article, “The Conservative Kerouac”, that summed up the depth of his Catholic roots quite well:

“The Catholic Church is a weird church,” Jack later wrote to his friend and muse Neal Cassady. “Much mysticism is sown broadspread from its ritual mysteries till it extends into the very lives of its constituents and parishoners.” It is impossible to overstate the influence of Catholicism on all of Kerouac’s work[...]The influence is so obvious and so pervasive, in fact, that Kerouac became justifiably incensed when Ted Berrigan of the Paris Review asked during a 1968 interview, “How come you never write about Jesus?” Kerouac’s reply: “I’ve never written about Jesus? … You’re an insane phony … All I write about is Jesus.”

But wasn’t Jack Kerouac, author of “Dharma Bums”, a Buddhist? He spent a long time flirting with Buddhism, in a similar way that Thomas Merton — who Kerouac loved — thought there was much common ground between Buddhism and orthodox Catholicism. But Buddhism ultimately held no sway on the man. Experiencing a nervous break down, he realized that “was the night of the end of Nirvana…I realized all my (years of studying) Buddhism had been words, comforting words, indeed, but when I saw those masses of devils racing for me.”

Now don’t get me wrong, we should be praying for the man’s soul. His life was an unhappy one. But he carried on a beautiful, Franciscan-like search to see the face of God, overwhelmed by the sense that all things are holy. There are few writers who have so clearly pointed out — to me, at least — man’s longing for the divine.

2. Chief Sitting Bull

This one made my 5 Things No One Knows Are Ridiculously Catholic list a little while ago, but I believe it worth the repost:

Somewhere in the bowels of a Grateful Dead apparel store, on the clothing rack next to the incense sticks, you’re bound to find a shirt with this guy on it…

…usually plastered along with a great quote like “The white man knows how to make everything, but he does not know how to distribute it.” And thus Chief Sitting Bull is claimed as a free-thinking, proto-liberal, tolerating sort of fellow who surely would’ve been down with abortion and all the rest. But it’s a conveniently cropped picture. Here’s the real deal:

Can you spot the difference? It’s the rocking of Jesus Christ dying on a cross around his neck. The best evidence points to Chief Sitting Bull as a baptized Catholic, though he was never fully received into the Church on account of having two wives and being unable to choose between the two. (You know how it is.)

3. Salvador Dali

Now Salvador Dali, by all rights, shouldn’t have ended up a Catholic. His father — atheist extraordinaire — put him in a state-sponsored school to help him avoid the idiotic teaching of priests. For most of his life, Dali looked like he was going to live up to his father’s expectations. This painting…

…is entitled “Sometimes I Spit With Pleasure on the Portrait of my Mother (The Sacred Heart)”. He often blamed the Church for his attitude towards sex — one of near-celibacy and really-weird voyeurism — making him the ideal liberated Catholic. He tried to kill himself at least twice. He held orgies, and was otherwise awkwardly fascinated with just about every orifice the human bodies around him had the misfortune to contain.

But against all odds, by the 1940′s, Dali became convinced that there must be a God. He expressed it paradoxically: “I believe in God but I have no faith. Mathematics and Science tell me that God must exist but I don’t believe it.” He lacked faith, but he could not deny that science, and especially quantum mechanics, was rendering materialism — the idea that the material world is all that exists — bunk. In 1947 he asked a Franciscan friar to exorcise him of a demon, and made him a crucifix as a gift for doing so. In 1949 he had an audience with Pope Pius X11, showing him this:

The Pope, recognizing it was really cool, blessed it.

In 1951 he wrote the excellent, prideful-to-the-point-of-hilarity, Mystical Manifesto, renouncing his surrealist contemporaries for creating art “directly from the tube of their biology without mixing in it even a bit of their heart or soul” and instead taking up the mysticism of the holy Saints, claiming that “the decadence of modern painting was a consequence of skepticism and lack of faith, the result of mechanistic materialism…” From the Manifesto:

A brilliant inspiration shows me that I have an unusual weapon at my disposal to help me penetrate to the core ofreality: mysticism -that is to say, the profound intuitive knowledge of what is, direct communication with the all, absolute vision by the grace of Truth, by the grace of God. More powerful than cyclotrons and cybernetic calculators, I can penetrate to the mysteries of the real in a moment… Mine the ecstasy! I cry.The ecstasy of God and Man. Mine the perfection, the beauty, that I might gaze into its eyes! Death to academicism, to the bureaucratic rules of art, to decorative plagiarism, to the witless incoherence of African art! Mine, St. Teresa of Avila!… In this state of intense prophecy it became clear to me that means ofpictorial expression achieved their greatest perfection and effectiveness in the Renaissance, and that the decadence of modern painting was a consequence of scepticism and lack of faith, the result of mechanistic materialism. By reviving Spanish mysticism I, Dali, shall use my work to demonstrate the unity of the universe, by showing the spirituality of all substance.”

And you know what? He really did. His work got pretty awesome. He didn’t become a Saint overnight though, and his conversion was messy, so don’t forget to pray for his salvation.

4. John Wayne

The Duke was raised Presbyterian, married thrice — each time to a Catholic — and converted to Catholicism, obtaining the state of grace a few days before his death. One of his grandsons is now a priest.

5. Nancy Pelosi

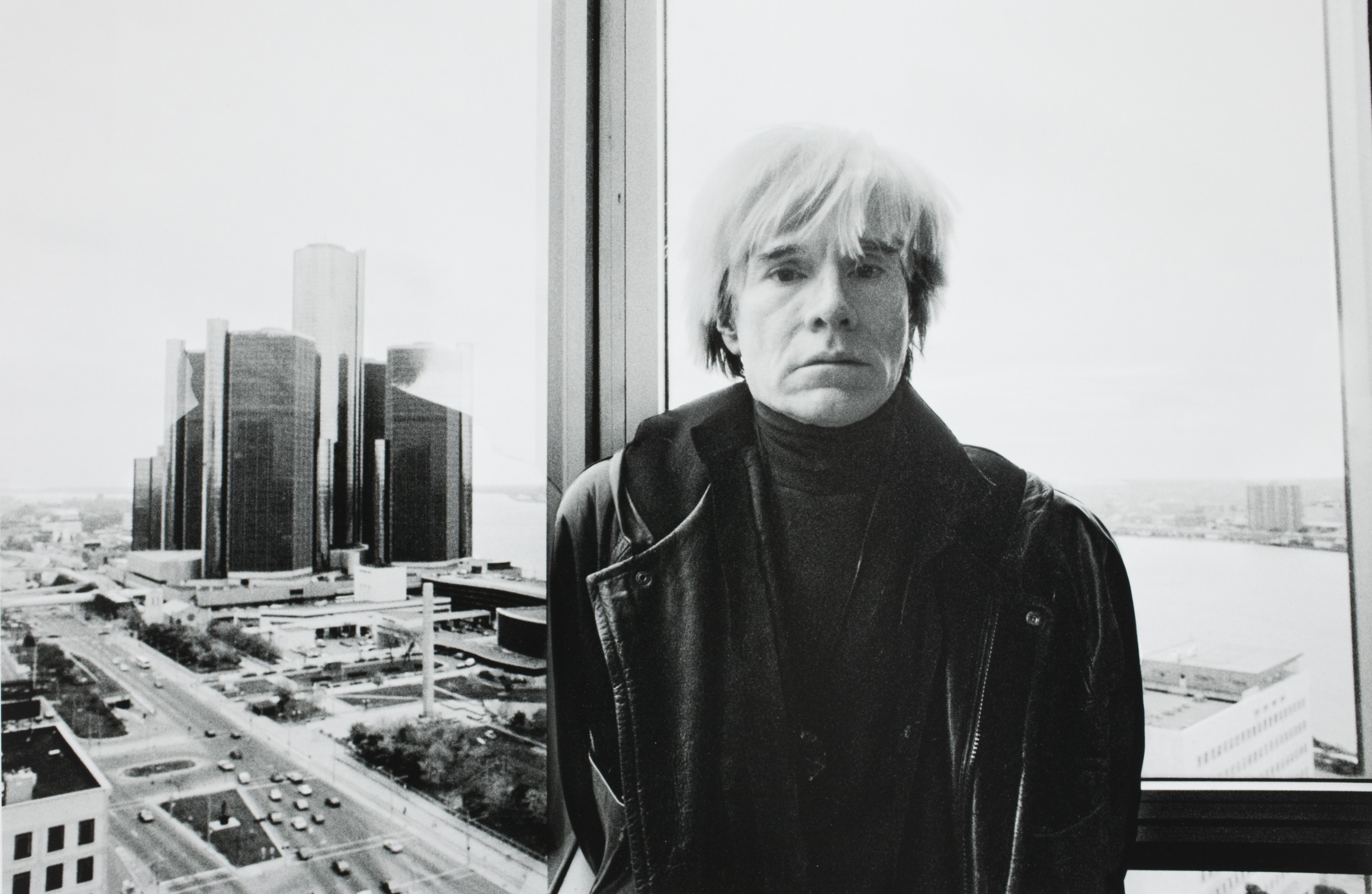

6. Andy Warhol

Religious beliefs

Warhol was a practicing Ruthenian Rite Catholic. He regularly volunteered at homeless shelters in New York, particularly during the busier times of the year, and described himself as a religious person.[93] Many of Warhol's later works depicted religious subjects, including two series, Details of Renaissance Paintings (1984) and The Last Supper (1986). In addition, a body of religious-themed works was found posthumously in his estate.[93]

During his life, Warhol regularly attended Mass, and the priest at Warhol's church, Saint Vincent Ferrer, said that the artist went there almost daily,[93] although he was not observed taking communion or going to confession and sat or knelt in the pews at the back.[85] The priest thought he was afraid of being recognized; Warhol said he was self-conscious about being seen in a Latin Rite church crossing himself "in the Orthodox way" (right to left instead of the reverse).[85]

His art is noticeably influenced by the eastern Christian tradition which was so evident in his places of worship.[93]

Warhol's brother has described the artist as "really religious, but he didn't want people to know about that because [it was] private". Despite the private nature of his faith, in Warhol's eulogy John Richardson depicted it as devout: "To my certain knowledge, he was responsible for at least one conversion. He took considerable pride in financing his nephew's studies for the priesthood".[93]

6. Tennessee Williams

"Tennessee Williams Is Now Catholic"

***

7.) Oscar Wilde

Deathbed Convert

"The Catholic Church is for saints and sinners alone. For respectable people, the Anglican Church will do.”

"I do believe in anything, provided it is incredible. That's why I intend to die a Catholic, though I never could live as one."

***

8.) Dave Brubeck

As Deacon Greg Kandra points out (and I noted in this May 2011 post), Brubeck was also a convert, in 1980, to the Catholic Church. This 2009 article in St. Anthony Messenger states:

To Hope! A Celebration was Brubeck’s first encounter with the Roman Catholic Mass, written at a time when he belonged to no denomination or faith community. It was commissioned by Our Sunday Visitor editor Ed Murray, who wanted a serious piece on the revised Roman ritual, not a pop or jazz Mass, but one that reflected the American Catholic experience.

The writing was to have a profound effect on Brubeck’s life. A short time before its premiere in 1980 a priest asked why there was no Our Father section of the Mass. Brubeck recalls first inquiring, “What’s the Our Father?” (he knew it as The Lord’s Prayer) and saying, “They didn’t ask me to do that.”

He resolved not to make the addition that, in his mind, would wreak havoc with the composition as he had created it. He told the priest, “No, I’m going on vacation and I’ve taken a lot of time from my wife and family. I want to be with them and not worry about music.”

“So the first night we were in the Caribbean, I dreamt the Our Father,” Brubeck says, recalling that he hopped out of bed to write down as much as he could remember from his dream state. At that moment he decided to add that piece to the Mass and to become a Catholic.

He has adamantly asserted for years that he is not a convert, saying to be a convert you needed to be something first. He continues to define himself as being “nothing” before being welcomed into the Church.

His Mass has been performed throughout the world, including in the former Soviet Union in 1997 (when Russia was considering adopting a state religion) and for Pope John Paul II in San Francisco during the pontiff’s 1987 pilgrimage to the United States. At the latter celebration, Brubeck was asked to write an additional processional piece for the pope’s entrance into Candlestick Park.

Again, it was a dream that led him to accept a sacred music project that he initially refused as not workable. The dream “was more of a realizing that I could write what I wanted for the music,” Brubeck says.

“They needed nine minutes and they gave me a sentence, ‘Upon this rock I will build my Church and the jaws of hell cannot prevail against it.’ So rather than dream musically, I dreamed practically that Bach would have taken one sentence in a chorale and fugue, as he often did, and that was the answer,” he says. “So I decided that I would do that piece for the pope,” which is known as “Upon This Rock.”

If I might, here are some thoughts from a post I wrote last year on the "catholicity of jazz", with a reference to Brubeck:

Brubeck composed a piece, "To Hope! A Celebration Mass" in 1996 that seems to have a much more classical/European sound to it. Regardless, I've long said that I never want to hear jazz at Mass, now matter how well it is played or composed, for while jazz is very beautiful, powerful, and even spiritual (in the best sense of that word), it's very nature—improvisational, largely profane (in the correct sense of that word)—is not well-suited, in my judgment, to liturgical settings.

But I would also insist that outside of liturgical settings, good jazz is good music, which means it is an artistic expression in keeping with Catholicism, which prizes and recognizes all that is good, true, and beautiful. Personal tastes differ, it goes without saying, and I can only take a little bit of Ornette Coleman or Cecil Taylor before I turn to the Blue Note albums of the 1950s and '60s, or the trio albums of Keith Jarrett, or the recent works of Joshua Redman, Brad Mehldau, Roy Hargrove, and so forth. Great jazz, to my mind and ear, is a marvelous combination of structure and improvisation, where intelligent musical conversation takes place upon a chosen, mutual theme, revealing both the individual thoughts/voices of those participating, as well as the deeper meaning and heart of the piece they are playing. It is a music that recognizes and honors and draws upon tradition while speaking about and within that tradition in the here and now. In my mind, jazz bears a certain analogy to the human condition: we are creatures endowed with great freedom, but freedom is to be exercised in pursuing the good, recognizing and respecting the limits and boundaries of our nature and of creation as established by God the Creator.